Antibiotics and Antibiotic Resistance

Antibiotics are one of the most important medical breakthroughs of the 20th century.1

They have revolutionized healthcare by making it possible to effectively treat bacterial infections. Before antibiotics, even minor infections could be life-threatening, and medical procedures and surgeries were much riskier due to the high chance of infection. As a consequence, antibiotics have saved countless lives.

But antibiotic resistance challenges their effectiveness. The overuse and misuse of antibiotics have hastened this growing global threat that makes it harder and more costly to treat infections.

The use of antibiotics isn't limited to human medicine: antibiotics are widely used in livestock farming, often as a cheap substitute for better hygiene standards.

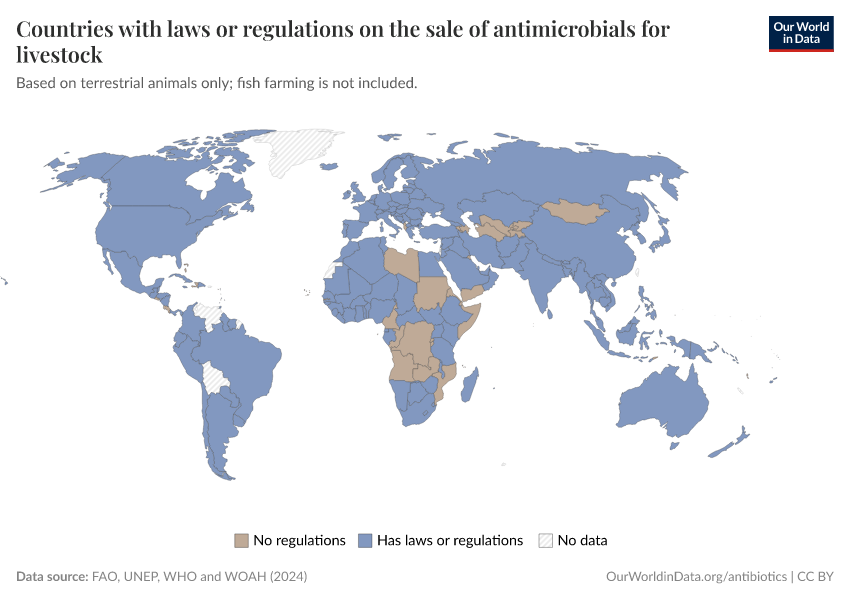

The world can combat resistance by using antibiotics more carefully, developing new drugs, regulating antibiotic usage in livestock, and ensuring better access to diagnostics and treatments.

On this page, we explore the history, impact, and future of antibiotics, and present global data and research on antibiotics and antibiotic resistance.

Research & Writing

- What was the Golden Age of Antibiotics, and how can we spark a new one?

- How do antibiotics work, and how does antibiotic resistance evolve?

- Large amounts of antibiotics are used in livestock, but several countries have shown this doesn’t have to be the case

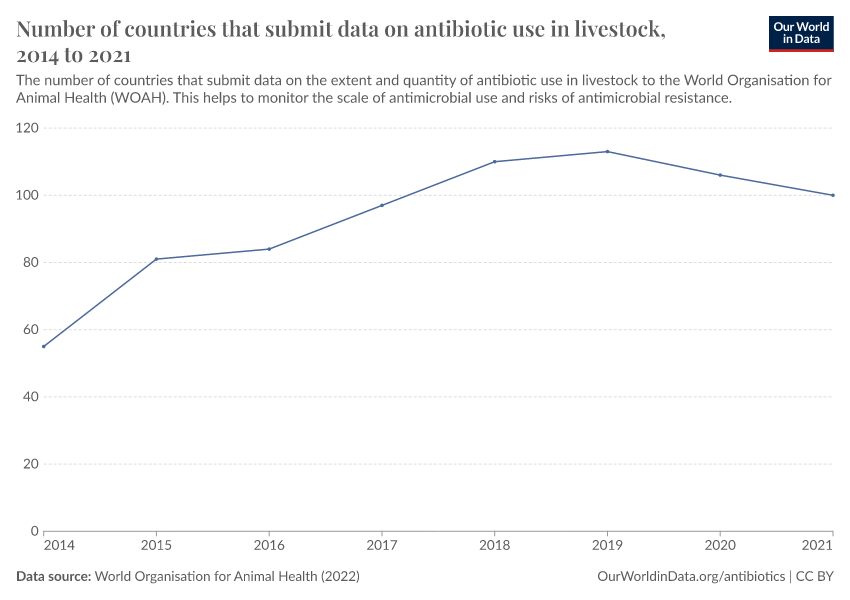

- Public data on antibiotic use in livestock is incomplete, making it difficult to track how much is used and where

See all interactive charts on antibiotics ↓

The Golden Age of Antibiotics was a period of rapid antibiotic discovery

The modern scientific journey of antibiotics began in the early 20th century with the microbiologist Paul Ehrlich. He searched for potential medicines that could target microbes without harming human cells. In 1910, after testing hundreds of compounds, he achieved a breakthrough with salvarsan — the first effective treatment for syphilis and the first synthetic antibiotic.2

Another milestone came in 1928 when Alexander Fleming observed fungal mold on a contaminated Petri dish that killed bacteria. He had discovered penicillin.

Unfortunately, scaling up its production took years.3 In the late 1930s and early 1940s, the U.S. War Production Board coordinated efforts to improve fermentation, organize trials, foster collaboration, and lift patent restrictions — which sped up development. By 1945, they had succeeded, making penicillin widely available.4

Another breakthrough was also achieved during this time: scientists discovered the potential of actinomycetes, a group of soil-dwelling bacteria, which eventually became the source of many antibiotics like streptomycin, tetracyclines, and erythromycin.5

The period between the 1940s and 1960s is known as “the golden age of antibiotics”, as intense research into natural and synthetic compounds led to the rapid discovery of many new antibiotics.

As the timeline shows, almost two-thirds of all antibiotic drug classes were developed and introduced during the golden age of antibiotics.

By the 1970s, however, the antibiotic pipeline slowed down. Pharmaceutical companies shifted focus to chronic disease treatments, which were more profitable, especially as bacterial resistance to antibiotics grew. In addition, efforts to spot new antibiotics by screening organisms for antibiotic activity often led to reidentifying the same compounds already discovered by others.2

Read more in our article:

Antibiotics have greatly reduced infection death rates

Antibiotics have been effective against a wide range of bacterial infections, and have also helped make childbirth, cancer treatments, and medical procedures — such as surgeries and organ transplants — much safer.

Penicillin’s availability meant that streptococcal infections, syphilis, and pneumonia could be effectively treated.6 Erythromycin followed, treating respiratory infections like bronchitis and pneumonia, as well as skin and ear infections. Tetracyclines had an even broader range of uses, targeting proteins common in many bacteria and some parasites.7

The most evident example of their positive impact comes from sulfonamides (commonly known as “sulfa drugs”), the second class of antibiotics developed. They were made available in the United States in 1937, before many other new treatments, which makes it possible to see their impact on death rates from diseases. This is visualized in the chart below.

Sulfa antibiotics could effectively treat infections such as Streptococcal pneumonia, scarlet fever, and urinary tract infections; they could also be used during C-sections to reduce the risks of infection and sepsis.8

Researchers Seema Jayachandran, Adriana Lleras-Muney, and Kimberly V. Smith estimated their impact on death rates from various diseases, as shown in the chart above.9

Death rates from infectious diseases had already declined over the previous decades in the United States due to general improvements in hygiene, sanitation, and healthcare. But they dropped even more steeply after sulfa antibiotics became available.

Compared to previous trends, the researchers estimate that sulfa antibiotics resulted in a 36% decline in death rates from maternal conditions, a 24% decline from influenza and pneumonia, and a 65% decline in scarlet fever.10

Because of these effects, it’s estimated that they led to a 3% decline in death rates overall, translating to a rise in the average life expectancy of around half a year — a remarkable impact from a single group of antibiotics.9

The use of antibiotics could greatly lower child mortality and disease in poorer countries

In many poorer countries, diseases like pneumonia and diarrhea are the leading causes of child deaths. These illnesses are often caused by bacteria and are treatable with antibiotics but continue to claim lives because many families lack access to essential medicines and healthcare.

One example of a life-saving program has been the mass drug administration (MDA) of azithromycin, a broad-spectrum antibiotic for children in poorer regions.11

In several large randomized trials conducted in different African countries — Niger, Burkina Faso, Tanzania, and Malawi — giving azithromycin tablets to children once or twice a year reduced child mortality rates by around 15%.12 That’s a very large reduction for a single antibiotic.

Azithromycin’s effectiveness comes from its effect on a wide range of bacteria, its rapid spread to multiple organs, and the high prevalence of bacterial infections in these regions.13

Beyond saving lives, antibiotics have helped reduce trachoma, a painful bacterial eye infection that can lead to blindness. Large-scale efforts to distribute azithromycin tablets, provide clean water, and improve hygiene substantially reduced the prevalence of trachoma in many African regions, as shown in the map below.

This shows that targeted or high-impact uses of antibiotics can be very effective, although monitoring for antibiotic resistance is also essential to maintain high efficacy over time.15

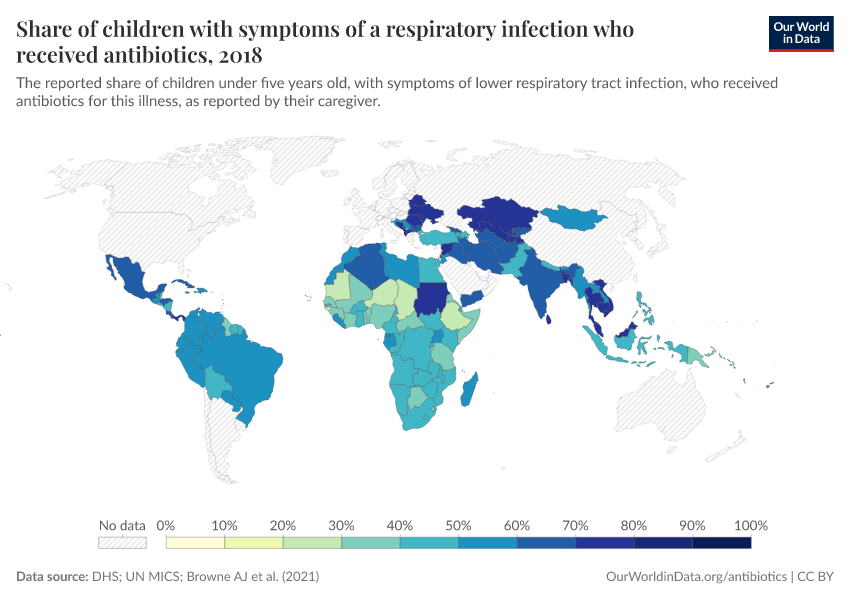

Antibiotic usage varies greatly around the world

The map below shows the usage of antibiotics to treat children with respiratory infections. Data comes from large-scale surveys such as the DHS and UN MICS.

This counts all reported respiratory infections, which means it can also include antibiotics used to treat infections caused by viruses and other pathogens, for which antibiotics are ineffective.

As you can see, in several countries in Eastern Europe and Central and South Asia, it’s common for children to receive antibiotics for respiratory infections. But it’s much less common in parts of Africa, where as few as one in four children receive them in some countries.

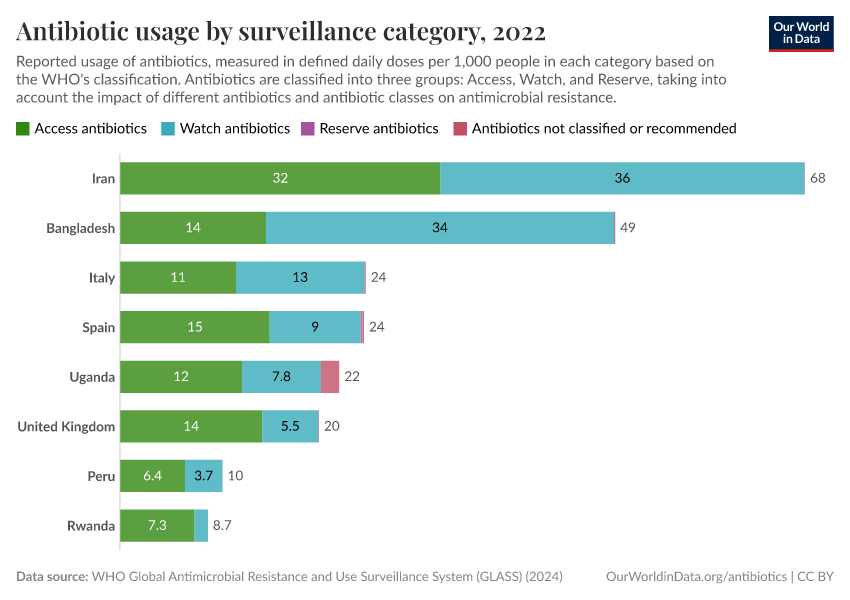

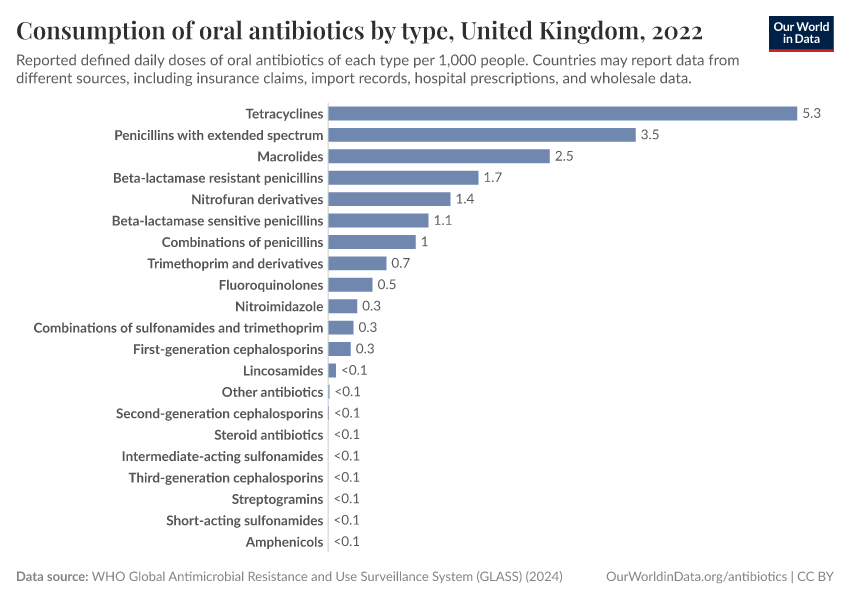

What about antibiotic usage in the population as a whole?

Unfortunately, the data for different countries relies on different sources, including insurance claims, import records, hospital prescriptions, and wholesale data, and may not be representative of the population. This can limit comparability.

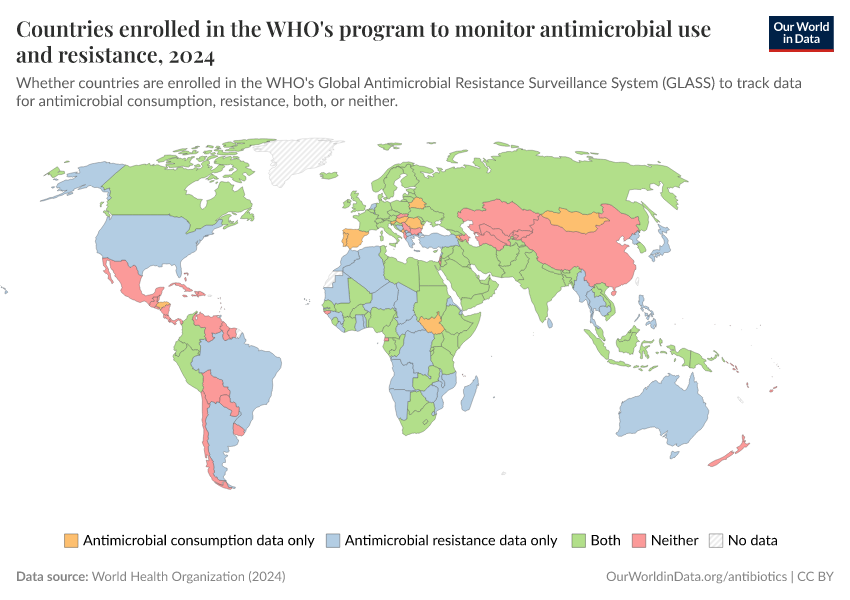

The map below shows the data collected by the World Health Organization’s GLASS system, which tracks national antimicrobial use and resistance worldwide. It shows the average level of antibiotic consumption in each country, as measured by “defined daily doses” (DDDs) per 1,000 people.

For example, five DDDs correspond to the daily amount of antibiotics typically used to treat an infection in five people.

As you can see, the recorded usage of antibiotics varies widely, with high rates in parts of Asia and some countries in Africa and lower rates in parts of Europe. It can be difficult to make direct comparisons with the previous map, which showed antibiotic usage among children from large standardized surveys, while this data comes from a range of sources.

The map also shows data for many countries as missing, reflecting the limited national data collection and reporting on antibiotic usage.

There are likely multiple reasons for these differences. One is that rates of infectious diseases vary widely: for example, tuberculosis rates are around 10 times higher in sub-Saharan Africa than in Europe.

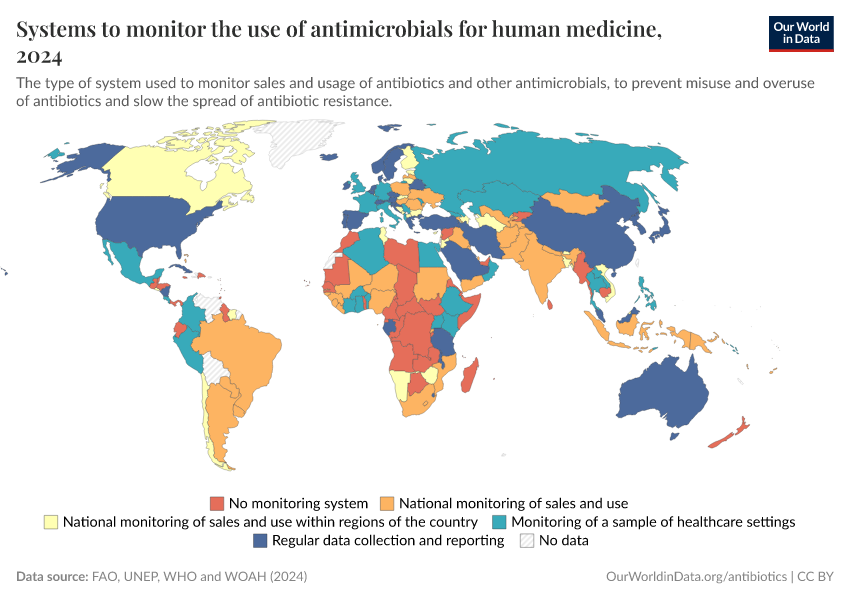

In addition, several countries, especially in Europe, use “antibiotic stewardship programs” to monitor and limit the overuse of antibiotics.

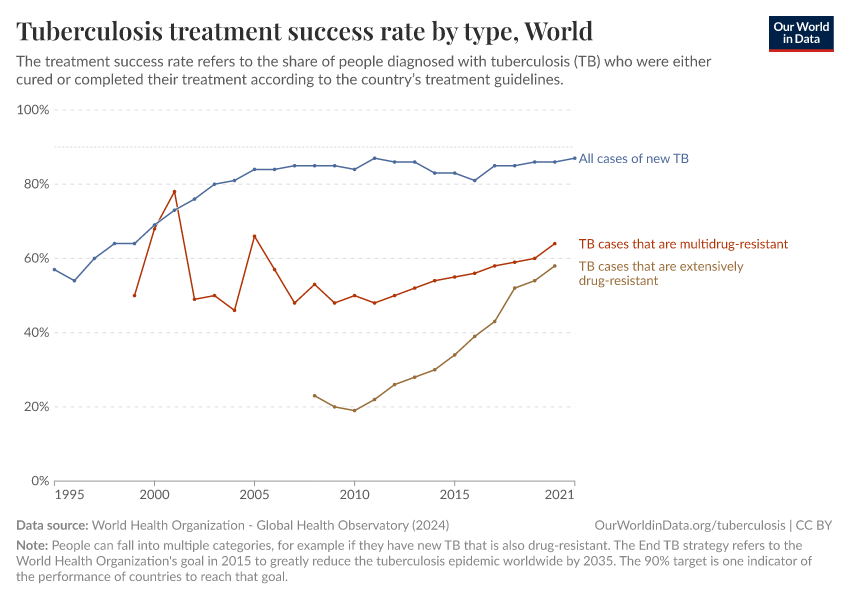

Antibiotic resistance threatens our ability to treat common infections

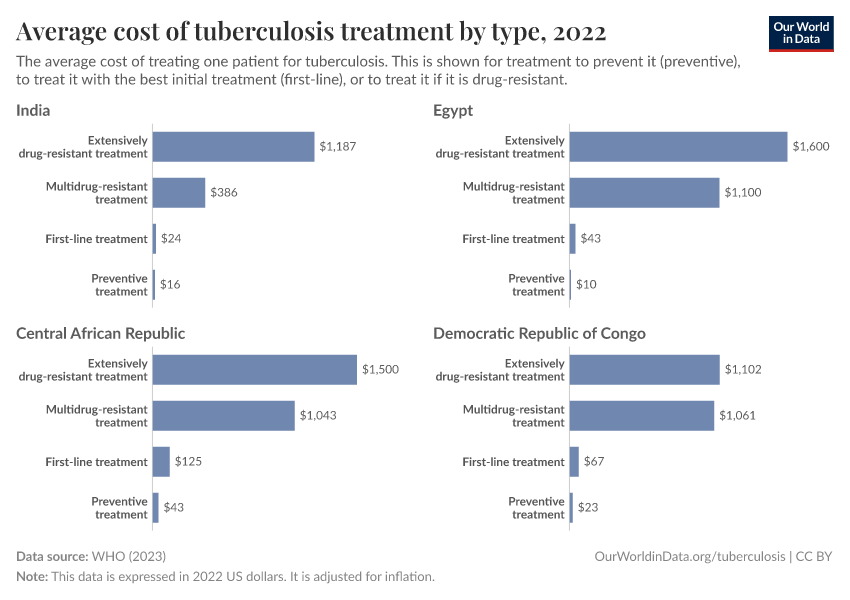

When bacteria evolve to evade antibiotics, common infections become much harder to treat, and life-saving medical procedures and surgeries can become much more dangerous. Resistant bacteria can also spread, leading to infections that are harder and more expensive to treat and often require medications with greater side effects.

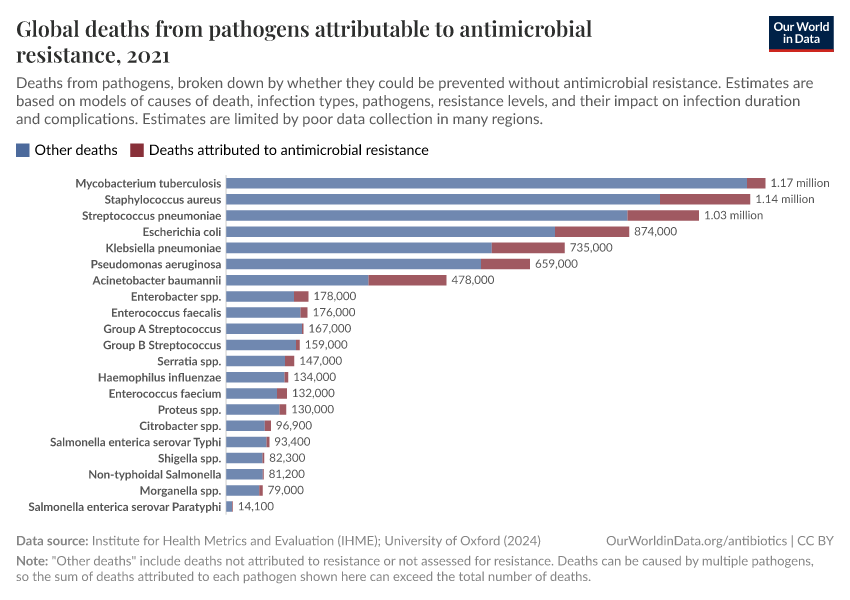

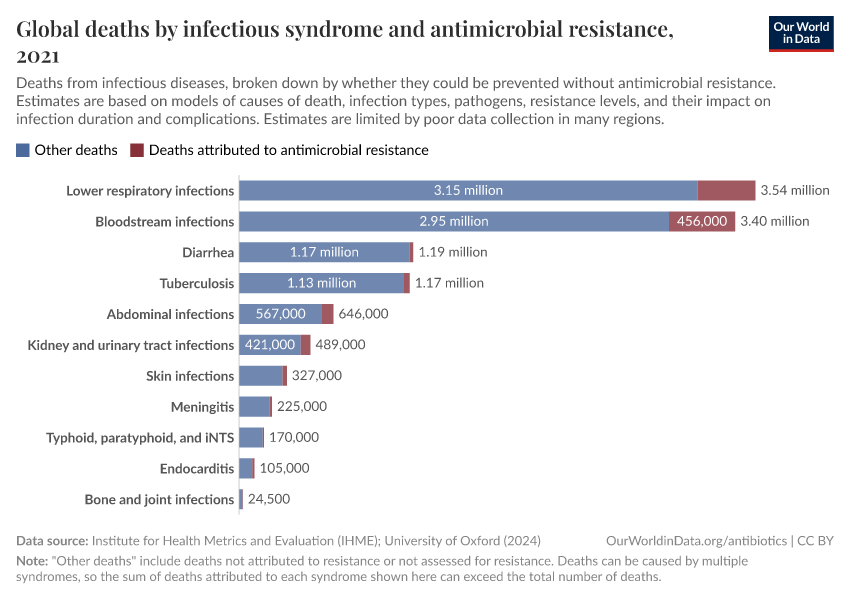

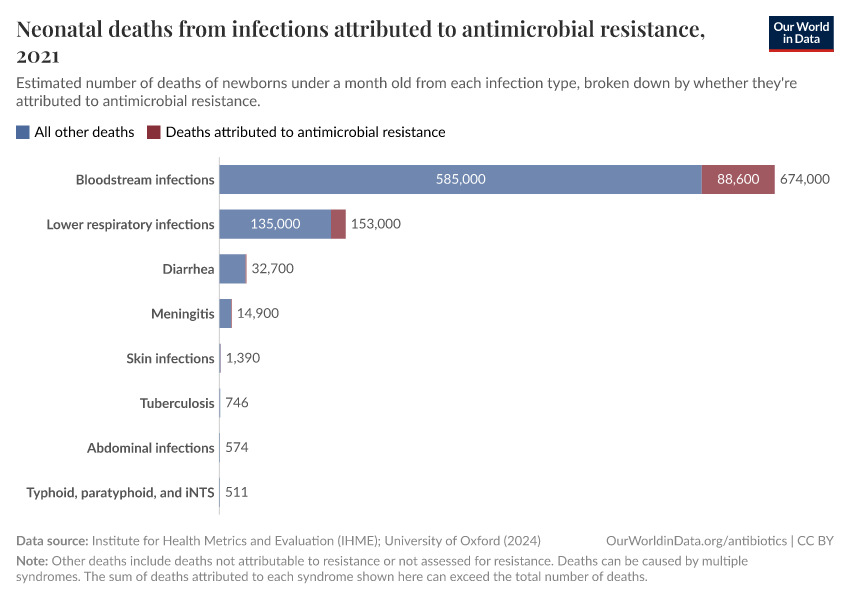

The chart here shows estimates of the number of deaths caused by infectious syndromes, broken down by whether the deaths are attributed to antibiotic resistance — meaning they would have been prevented if the infection wasn’t resistant.

As you can see, deaths caused by antibiotic resistance are most common for bloodstream infections and lower-respiratory infections.

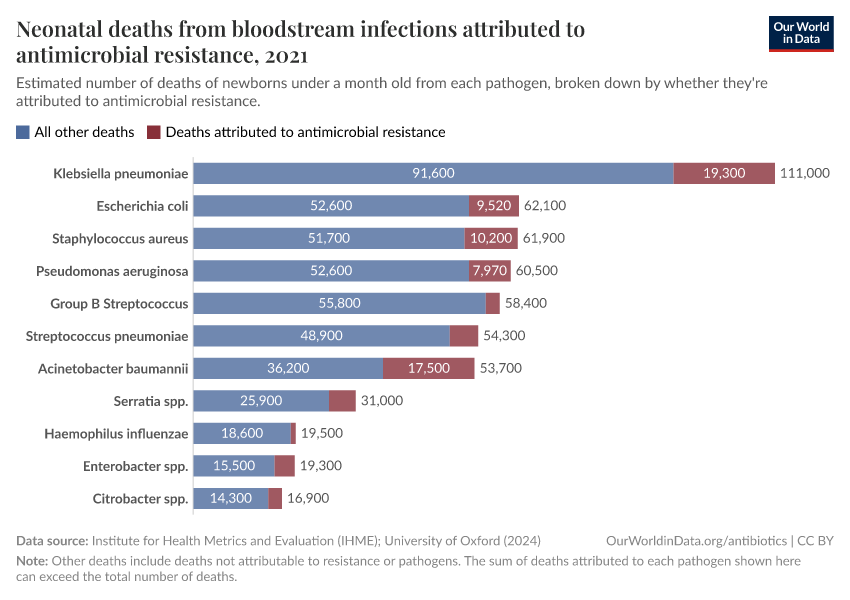

In this related chart, you can see these estimates broken down by different pathogens:

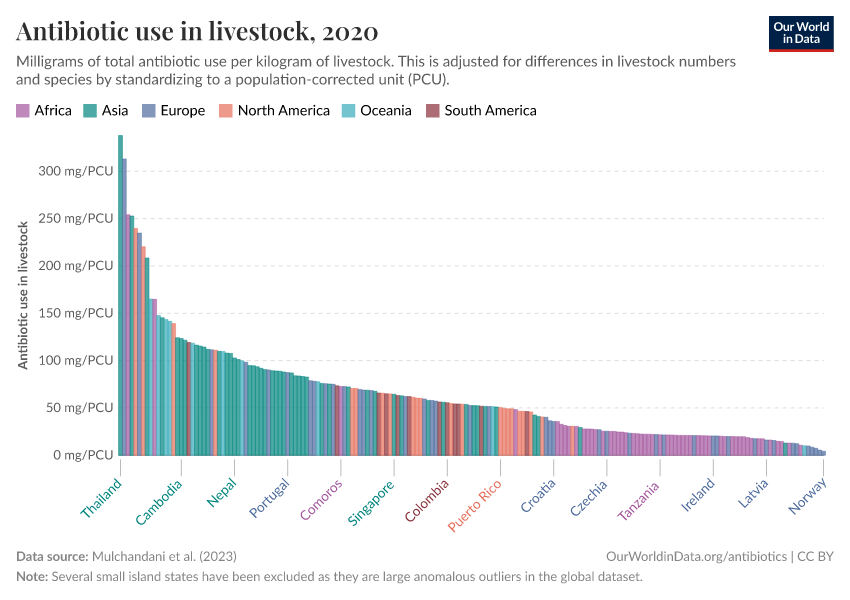

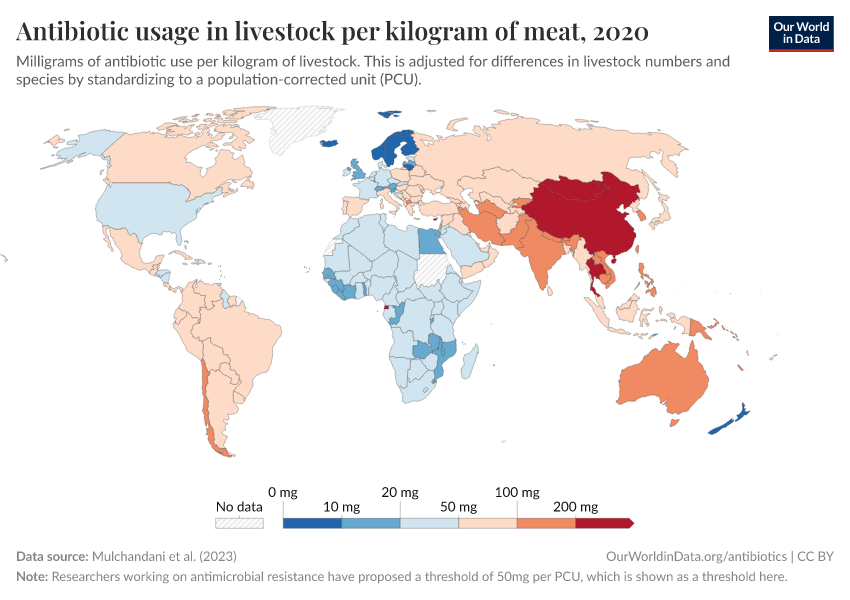

A large share of antibiotics are used for livestock, often as a substitute for more hygienic conditions

Globally, it’s estimated that at least two-thirds of antibiotics are used for livestock.16

Because intensive farming keeps animals in cramped and unsanitary conditions, antibiotics are often used as a cheaper substitute for better living conditions and hygiene.

However, overuse can lead to the evolution and spread of antibiotic-resistant bacteria, threatening both animal and human health. Resistant pathogens can spread through contaminated meat and dairy, making some diseases harder to treat.

Antibiotic use varies widely between animals. Antibiotics are used more intensively for pigs and sheep than chickens and cattle17, partly due to their farming conditions and longer lifespans.

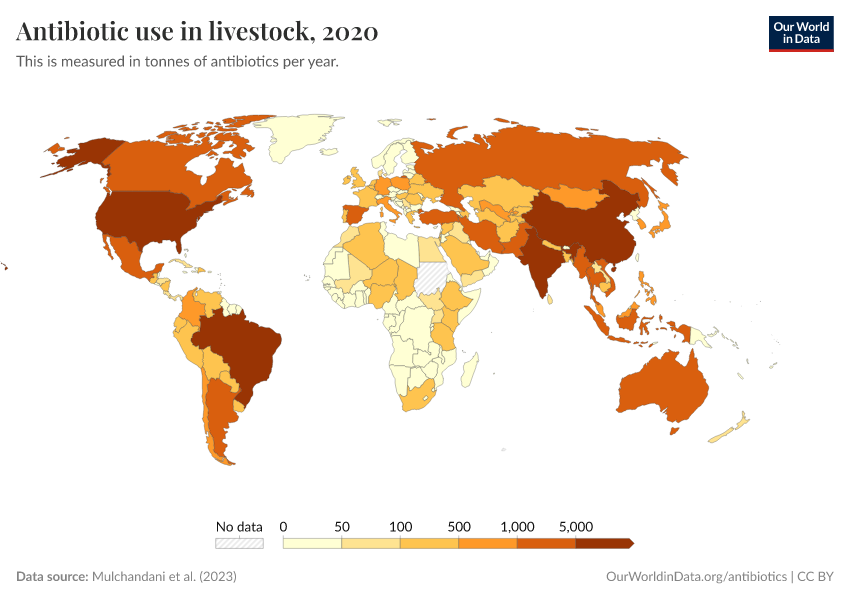

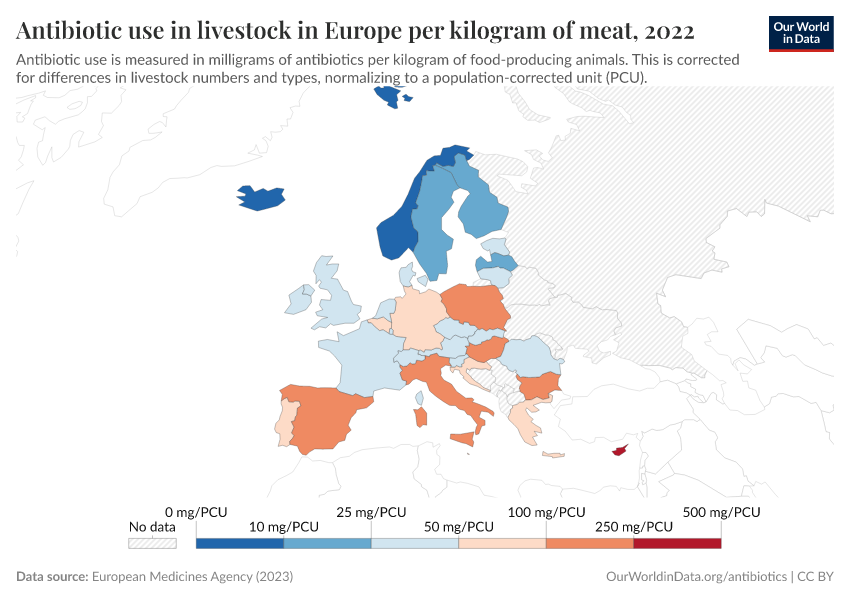

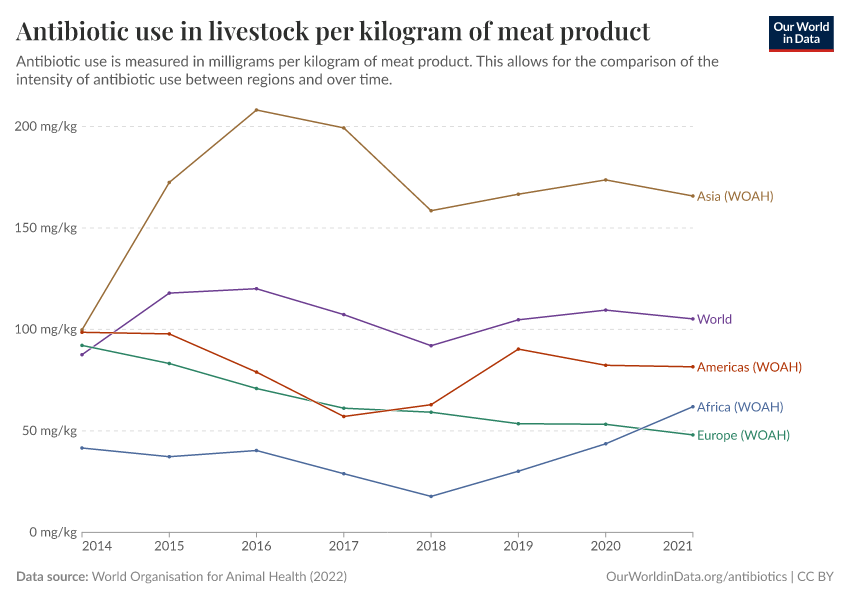

Usage also varies around the world, as you can see in the map below. The intensity of antibiotic use is highest in Asia, Australasia, and the Americas. In contrast, antibiotic use is lower in Africa due to lower access, and in Europe, partly due to regulation.

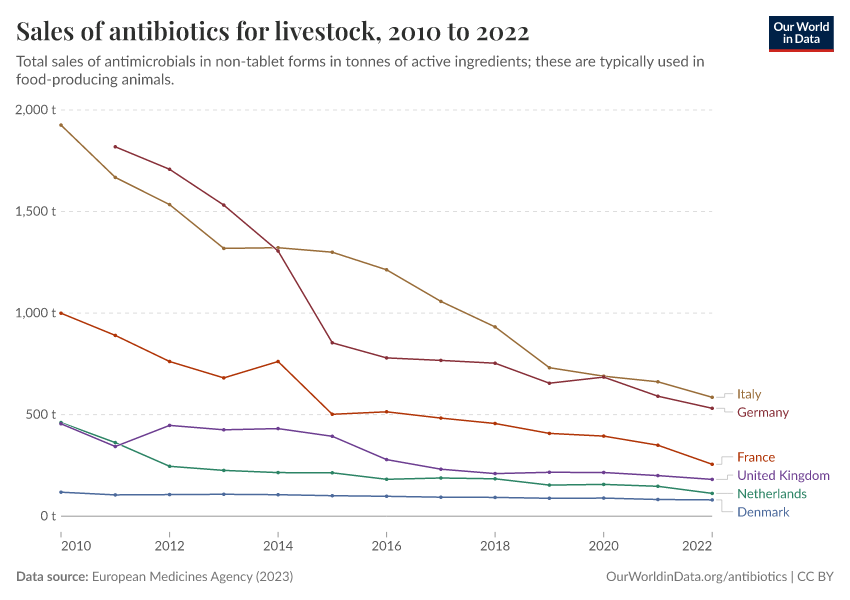

The chart below shows that antibiotic sales for livestock have dropped significantly in several European countries.

Several policies have contributed to this, such as requirements for veterinarian prescriptions, taxes on antibiotic sales, and prohibiting discounts. In addition, many farms have shifted to using slower-growing animal breeds without harming farm productivity.

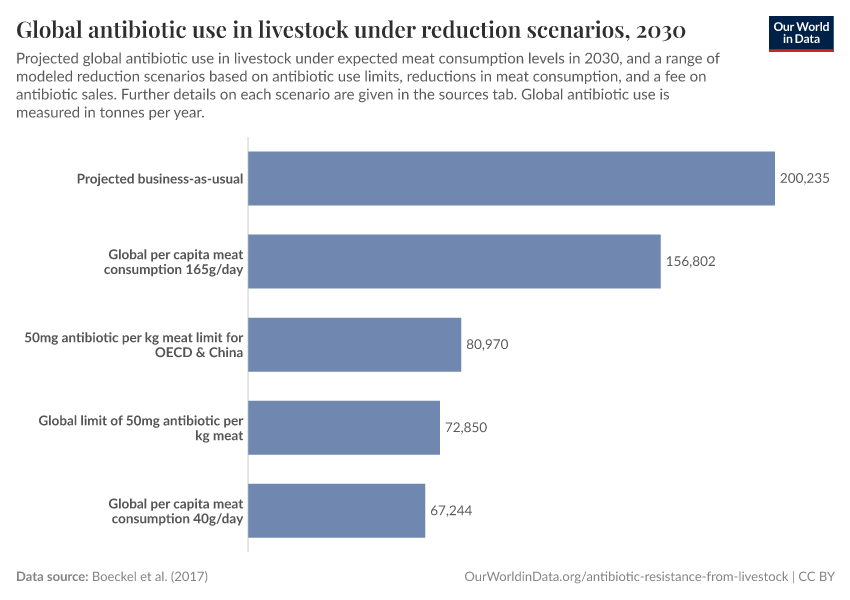

There are several ways to reduce antibiotic overuse in livestock: improving sanitary conditions for animals, using antibiotics only when necessary, and reducing meat consumption.

Cutting meat consumption, even moderately, could dramatically lower antibiotic use while also benefiting the environment and public health.

Read more in our article:

What can we do to tackle antibiotic resistance?

Antibiotic resistance is a growing challenge, but there are several ways to tackle it.

This includes public health measures, improved diagnostic technology and prescription practices, antibiotic stewardship programs, and economic incentives to develop new antibiotics.

Public health measures to reduce the spread of bacterial infections

Preventing bacterial infections is one of the most effective ways to combat antibiotic resistance. Vaccination programs, access to clean water and sanitation, and better hygiene practices can significantly reduce infections.

For example, vaccines against Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae can protect people from infectious diseases and reduce the need for antibiotics.

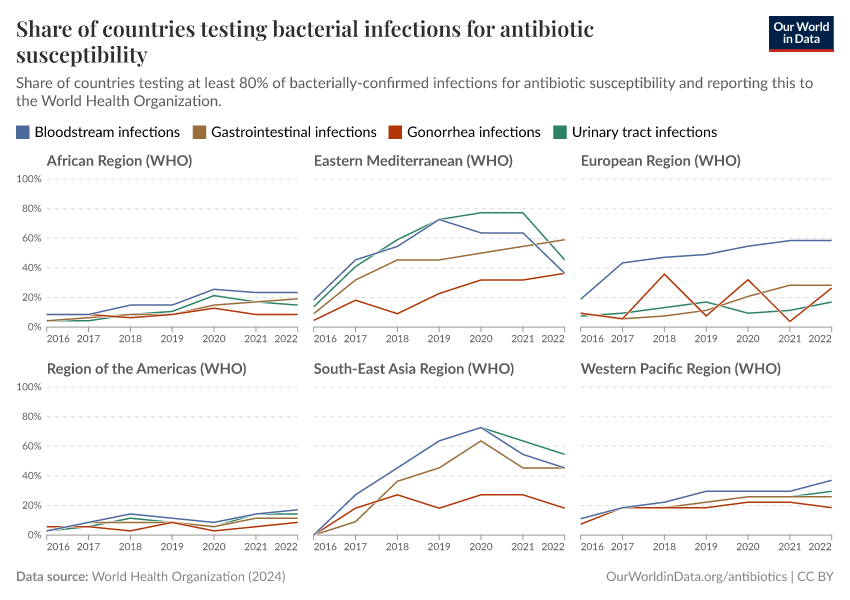

Improvements in diagnosis, testing, and usage

It can often take several days to identify infections and to know whether they’re treatable with antibiotics. These delays frequently lead doctors to prescribe broad-spectrum antibiotics, which can be ineffective and fuel resistance.

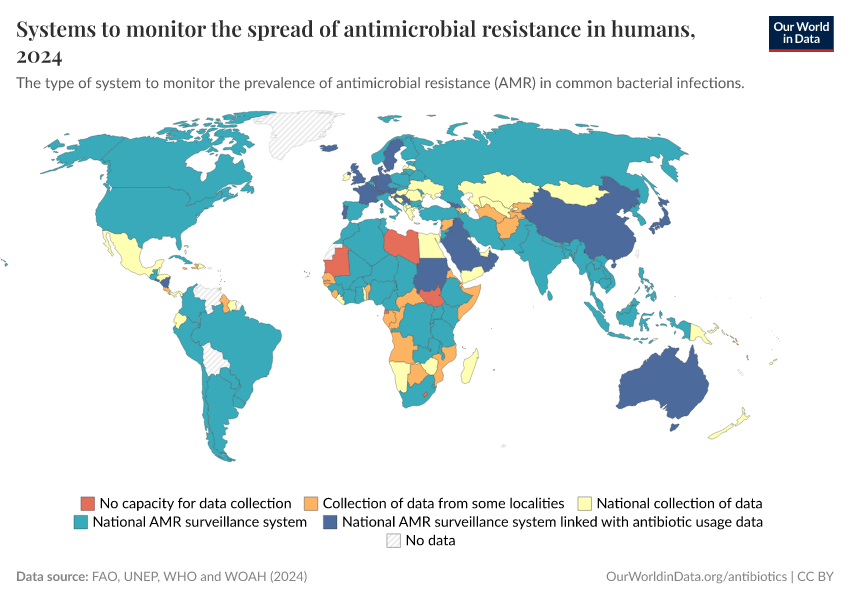

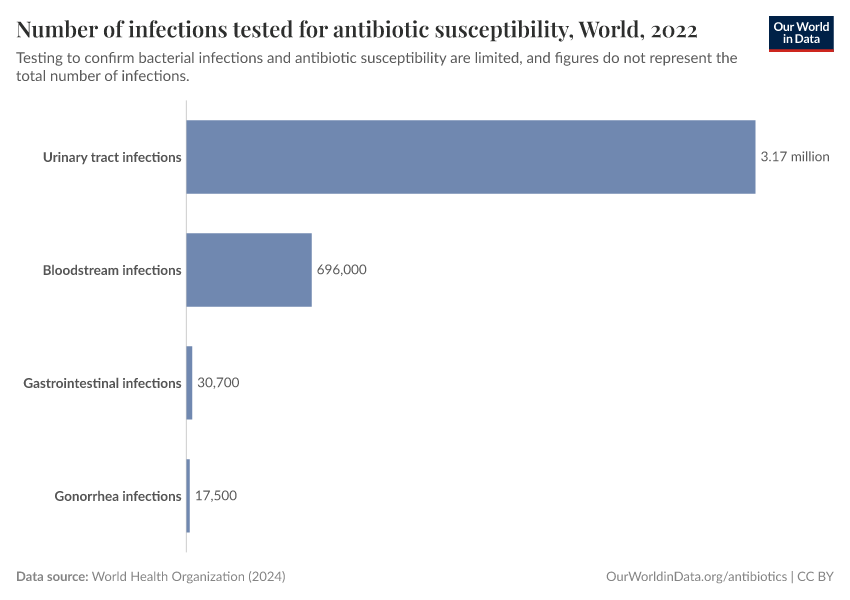

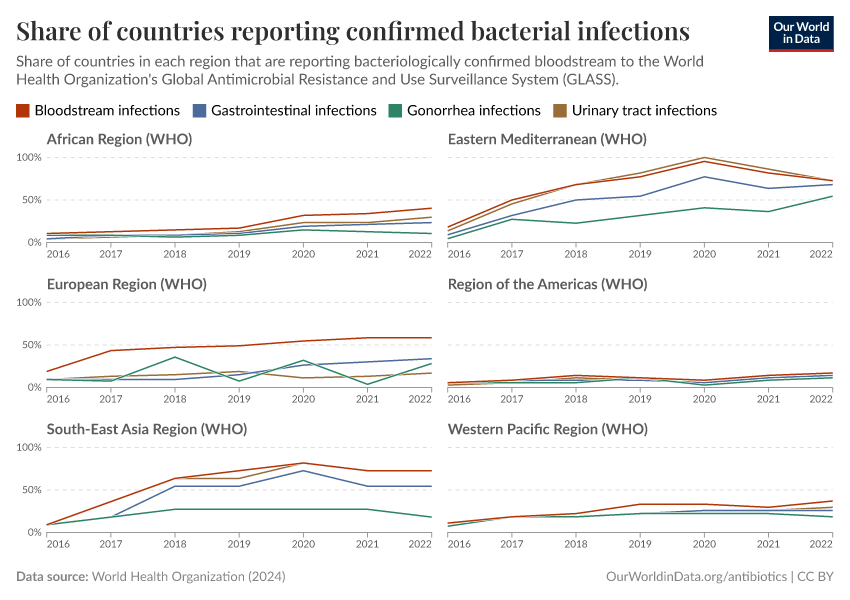

But testing for bacterial infections and resistance is limited in many countries. Without bacterial testing, it’s difficult to identify whether the disease is caused by a bacterium rather than another pathogen, such as a virus or parasite — for which antibiotics may be ineffective.

Without resistance testing, we can’t quickly identify whether antibiotics are less effective against an infection, help track the spread of antibiotic resistance, and determine whether we’re making progress against it.

With new and faster diagnostic tools, healthcare workers can quickly determine whether an infection is bacterial, what type of bacteria is causing it, and which antibiotics are effective.

In many wealthier countries, antibiotic stewardship programs guide appropriate antibiotic use. These programs help healthcare workers decide when and which antibiotics to prescribe while introducing regulations to reduce misuse.

New antibiotic drug development

As resistance grows, new antibiotics are crucial. However, developing them is difficult, partly due to economic challenges. Antibiotics are typically used for short periods, sold at low prices, and reserved for limited use to slow resistance — making them less profitable for manufacturers.

Governments are addressing this with innovative funding models. For example, the UK is piloting a subscription system where health services pay an annual fee for antibiotic access, encouraging innovation without overuse.

Collaborative initiatives also fund projects to develop essential new drugs. These efforts could revitalize antibiotic discovery and ensure we have effective treatments in the future.

Read more in our article:

Antibiotics target different pathways, and bacteria can become resistant in different ways

In their natural environments, bacteria compete for resources like nutrients and space. Some bacteria produce antibiotics to suppress or kill competitors, giving them an advantage.18 They can target specific processes in bacterial cells that are critical for growth, reproduction, and stability, as the diagram below shows.

Unfortunately, bacteria can develop resistance to antibiotics. For example, they can produce enzymes called “beta-lactamases” that break down beta-lactam antibiotics.6 Bacteria can also produce proteins that pump tetracycline antibiotics out of their cells.21

These mechanisms tend to evolve within individuals (between days to months) but take longer to spread across populations (between weeks to years).

They allow bacteria to adapt to new antibiotics and share resistance mechanisms, including between different species.

Resistance mechanisms can come with costs: for example, producing enzymes like beta-lactamase or maintaining protein pumps can use up energy or resources, slowing bacterial growth.22

However, in the presence of antibiotics, the survival advantage can outweigh the trade-offs, allowing resistant bacteria to dominate over time.

You can read more in our article:

Key Charts on Antibiotics & Antibiotic Resistance

See all charts on this topicContinue reading on Our World in Data

Endnotes

The term “antibiotics” may have different meanings in the literature.

Sometimes antibiotics refer to only naturally derived antibacterials.

Sometimes antibiotics refer to small molecules that target bacteria (which includes natural and synthetic molecules), and are distinct from a range of other types of antibacterial agents, such as antibodies, bacteriophages, etc. We use this second definition.

Hutchings, M. I., Truman, A. W., & Wilkinson, B. (2019). Antibiotics: Past, present and future. Current Opinion in Microbiology, 51, 72–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mib.2019.10.008

Gaynes, R. (2017). The Discovery of Penicillin—New Insights After More Than 75 Years of Clinical Use. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 23(5), 849–853. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2305.161556

Sampat, B. N. (2023). Second World War and the Direction of Medical Innovation. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4422261

Gaynes, R. (2017). The Discovery of Penicillin—New Insights After More Than 75 Years of Clinical Use. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 23(5), 849–853. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2305.161556

Why We Should Reexamine the “Golden Age” of Antibiotics in Social Context. (2024). AMA Journal of Ethics, 26(5), E418-428. https://doi.org/10.1001/amajethics.2024.418

Baxter, J. P. (1946). Scientists Against Time (Vol. 1, Ch. 22). Little Brown. Available online.

Woodruff, H. B. (2014). Selman A. Waksman, Winner of the 1952 Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 80(1), 2–8. https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.01143-13

Hutchings, M. I., Truman, A. W., & Wilkinson, B. (2019). Antibiotics: Past, present and future. Current Opinion in Microbiology, 51, 72–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mib.2019.10.008

Bush, K., & Bradford, P. A. (2016). β-Lactams and β-Lactamase Inhibitors: An Overview. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Medicine, 6(8), a025247. https://doi.org/10.1101/cshperspect.a025247

Grossman, T. H. (2016). Tetracycline Antibiotics and Resistance. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Medicine, 6(4), a025387. https://doi.org/10.1101/cshperspect.a025387

Hollingsworth, A., Karbownik, K., Thomasson, M. A., & Wray, A. (2022). The gift of a lifetime: The hospital, modern medicine, and mortality (No. w30663). National Bureau of Economic Research. Available online.

Jayachandran, S., Lleras-Muney, A., & Smith, K. V. (2010). Modern Medicine and the Twentieth Century Decline in Mortality: Evidence on the Impact of Sulfa Drugs. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 2(2), 118–146. https://doi.org/10.1257/app.2.2.118

Jayachandran, S., Lleras-Muney, A., & Smith, K. V. (2010). Modern Medicine and the Twentieth Century Decline in Mortality: Evidence on the Impact of Sulfa Drugs. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 2(2), 118–146. https://doi.org/10.1257/app.2.2.118

Note that influenza and pneumonia are broad categories that include several respiratory infections. Influenza is caused by a virus and is unaffected by the use of antibiotics, while pneumonia can be caused by some viral and bacterial pathogens.

Other conditions, which are not treated by sulfa drugs, didn’t show a break in trend at this time point. This provides evidence that sulfa drugs were responsible for the steeper decline in infectious disease death rates.

Webster, J. P., Molyneux, D. H., Hotez, P. J., & Fenwick, A. (2014). The contribution of mass drug administration to global health: Past, present and future. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 369(1645), 20130434. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2013.0434

O’Brien, K. S., Arzika, A. M., Amza, A., Maliki, R., Aichatou, B., Bello, I. M., Beidi, D., Galo, N., Harouna, N., Karamba, A. M., Mahamadou, S., Abarchi, M., Ibrahim, A., Lebas, E., Peterson, B., Liu, Z., Le, V., Colby, E., Doan, T., … Lietman, T. M. (2024). Azithromycin to Reduce Mortality—An Adaptive Cluster-Randomized Trial. New England Journal of Medicine, 391(8), 699–709. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2312093

Keenan, J. D., Bailey, R. L., West, S. K., Arzika, A. M., Hart, J., Weaver, J., Kalua, K., Mrango, Z., Ray, K. J., Cook, C., Lebas, E., O’Brien, K. S., Emerson, P. M., Porco, T. C., & Lietman, T. M. (2018). Azithromycin to Reduce Childhood Mortality in Sub-Saharan Africa. New England Journal of Medicine, 378(17), 1583–1592. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1715474

Oldenburg, C. E., Ouattara, M., Bountogo, M., Boudo, V., Ouedraogo, T., Compaoré, G., Dah, C., Zakane, A., Coulibaly, B., Bagagnan, C., Hu, H., O’Brien, K. S., Nyatigo, F., Keenan, J. D., Doan, T., Porco, T. C., Arnold, B. F., Lebas, E., Sié, A., & Lietman, T. M. (2024). Mass Azithromycin Distribution to Prevent Child Mortality in Burkina Faso: The CHAT Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA, 331(6), 482. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2023.27393

Keenan, J. D., Arzika, A. M., Maliki, R., Boubacar, N., Elh Adamou, S., Moussa Ali, M., Cook, C., Lebas, E., Lin, Y., Ray, K. J., O’Brien, K. S., Doan, T., Oldenburg, C. E., Callahan, E. K., Emerson, P. M., Porco, T. C., & Lietman, T. M. (2019). Longer-Term Assessment of Azithromycin for Reducing Childhood Mortality in Africa. New England Journal of Medicine, 380(23), 2207–2214. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1817213

Oldenburg, C. E., Arzika, A. M., Amza, A., Gebre, T., Kalua, K., Mrango, Z., Cotter, S. Y., West, S. K., Bailey, R. L., Emerson, P. M., O’Brien, K. S., Porco, T. C., Keenan, J. D., & Lietman, T. M. (2019). Mass Azithromycin Distribution to Prevent Childhood Mortality: A Pooled Analysis of Cluster-Randomized Trials. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 100(3), 691–695. https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.18-0846

Parnham, M. J., Haber, V. E., Giamarellos-Bourboulis, E. J., Perletti, G., Verleden, G. M., & Vos, R. (2014). Azithromycin: Mechanisms of action and their relevance for clinical applications. Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 143(2), 225–245. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pharmthera.2014.03.003

Data and scripts to recreate these maps can be found on GitHub.

Renneker, K. K., Abdala, M., Addy, J., Al-Khatib, T., Amer, K., Badiane, M. D., Batcho, W., Bella, L., Bougouma, C., Bucumi, V., Chisenga, T., Dat, T. M., Dézoumbé, D., Elshafie, B., Garae, M., Goepogui, A., Hammou, J., Kabona, G., Kadri, B., … Ngondi, J. M. (2022). Global progress toward the elimination of active trachoma: An analysis of 38 countries. The Lancet Global Health, 10(4), e491–e500. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(22)00050-X

Kahn, R., Eyal, N., Sow, S. O., & Lipsitch, M. (2023). Mass drug administration of azithromycin: An analysis. Clinical Microbiology and Infection, 29(3), 326–331. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmi.2022.10.022

Getting a definitive figure here is difficult because of data reporting and transparency issues, which I will describe later.

Several of the most extensive studies on antimicrobial use in livestock cite 72% or 73%. This appears to come from a 2017 study by Thomas van Boeckel and colleagues.

It estimates that the intensity of antimicrobial use in humans is around 118 mg per kg. And 133 mg per kg in animals. When we multiply these figures by the estimated biomass (i.e., the weight) of humans and livestock, we get a total estimate for humans of around 35,000 tonnes a year, compared to 85,000 tonnes in livestock. That would mean livestock accounted for around 72% of total antibiotic use.

A recent study by Katie Tiseo and colleagues (2020) estimated that 66% of antimicrobials were used in livestock.

Van Boeckel, T. P., Pires, J., Silvester, R., Zhao, C., Song, J., Criscuolo, N. G., ... & Laxminarayan, R. (2019). Global trends in antimicrobial resistance in animals in low-and middle-income countries. Science.

Van Boeckel, T. P., Brower, C., Gilbert, M., Grenfell, B. T., Levin, S. A., Robinson, T. P., ... & Laxminarayan, R. (2017). Global trends in antimicrobial use in food animals. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Mulchandani, R., Wang, Y., Gilbert, M., & Van Boeckel, T. P. (2023). Global trends in antimicrobial use in food-producing animals: 2020 to 2030. PLOS Global Public Health.

Tiseo, K., Huber, L., Gilbert, M., Robinson, T. P., & Van Boeckel, T. P. (2020). Global trends in antimicrobial use in food animals from 2017 to 2030. Antibiotics.

After accounting for their larger size. The estimates are given per kilogram of meat, because larger animals tend to require higher volumes of antibiotics for treatment.

Aminov, R. I. (2009). The role of antibiotics and antibiotic resistance in nature. Environmental Microbiology, 11(12), 2970–2988. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1462-2920.2009.01972.x

Newman, D. J., & Cragg, G. M. (2016). Natural Products as Sources of New Drugs from 1981 to 2014. Journal of Natural Products, 79(3), 629–661. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jnatprod.5b01055

Van Der Meij, A., Worsley, S. F., Hutchings, M. I., & Van Wezel, G. P. (2017). Chemical ecology of antibiotic production by actinomycetes. FEMS Microbiology Reviews, 41(3), 392–416. https://doi.org/10.1093/femsre/fux005

European Commission: Joint Research Centre, Sanseverino, I., Loos, R., Navarro Cuenca, A., Marinov, D. et al., State of the art on the contribution of water to antimicrobial resistance, Publications Office, 2018, https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2760/771124

Hutchings, M. I., Truman, A. W., & Wilkinson, B. (2019). Antibiotics: Past, present and future. Current Opinion in Microbiology, 51, 72–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mib.2019.10.008

Grossman, T. H. (2016). Tetracycline Antibiotics and Resistance. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Medicine, 6(4), a025387. https://doi.org/10.1101/cshperspect.a025387

Souque, C., González Ojeda, I., & Baym, M. (2024). From Petri Dishes to Patients to Populations: Scales and Evolutionary Mechanisms Driving Antibiotic Resistance. Annual Review of Microbiology, 78(1), 361–382. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-micro-041522-102707

Cite this work

Our articles and data visualizations rely on work from many different people and organizations. When citing this topic page, please also cite the underlying data sources. This topic page can be cited as:

Saloni Dattani, Fiona Spooner, Hannah Ritchie, and Max Roser (2024) - “Antibiotics and Antibiotic Resistance” Published online at OurWorldinData.org. Retrieved from: 'https://ourworldindata.org/antibiotics' [Online Resource]BibTeX citation

@article{owid-antibiotics,

author = {Saloni Dattani and Fiona Spooner and Hannah Ritchie and Max Roser},

title = {Antibiotics and Antibiotic Resistance},

journal = {Our World in Data},

year = {2024},

note = {https://ourworldindata.org/antibiotics}

}Reuse this work freely

All visualizations, data, and code produced by Our World in Data are completely open access under the Creative Commons BY license. You have the permission to use, distribute, and reproduce these in any medium, provided the source and authors are credited.

The data produced by third parties and made available by Our World in Data is subject to the license terms from the original third-party authors. We will always indicate the original source of the data in our documentation, so you should always check the license of any such third-party data before use and redistribution.

All of our charts can be embedded in any site.