Biodiversity

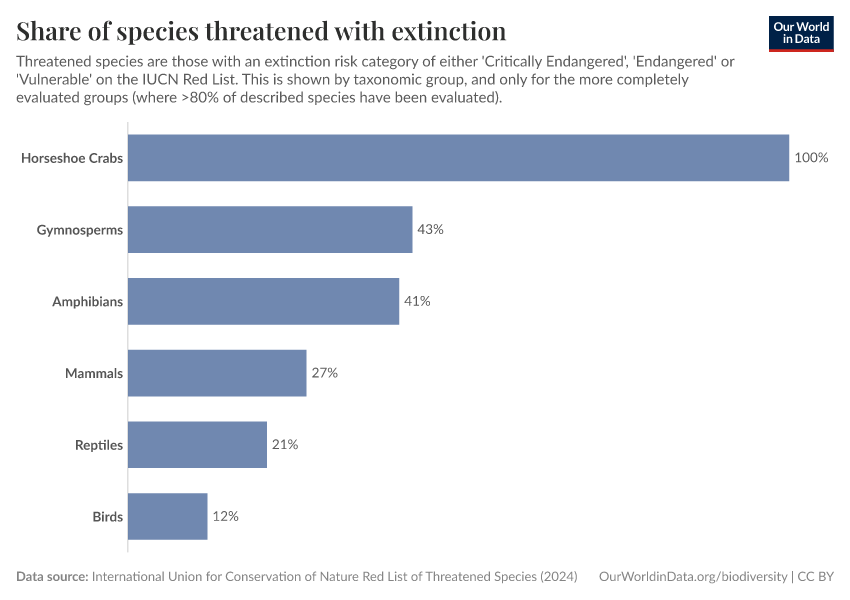

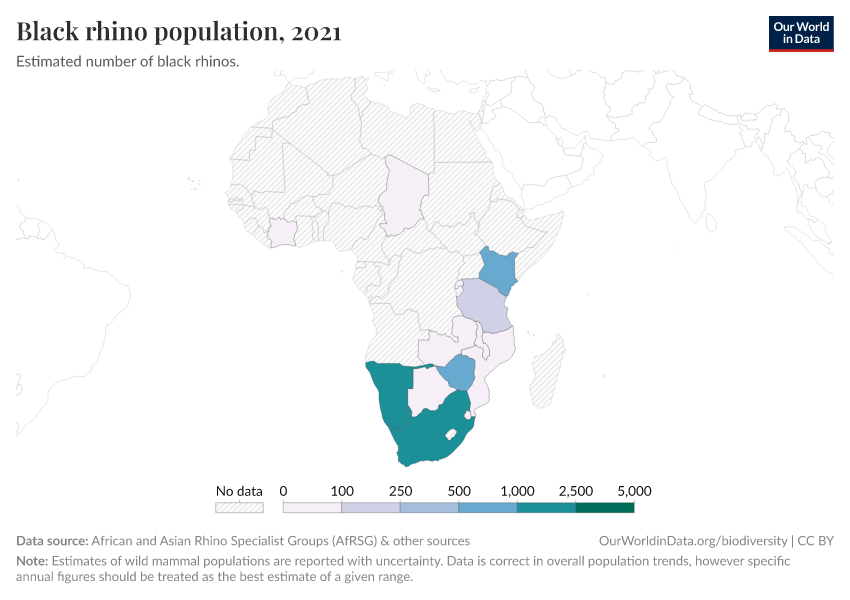

Explore the diversity of wildlife across the planet. What are species threatened with? What can we do to prevent biodiversity loss?

Most of our work on Our World in Data focuses on data and research on human well-being and prosperity.

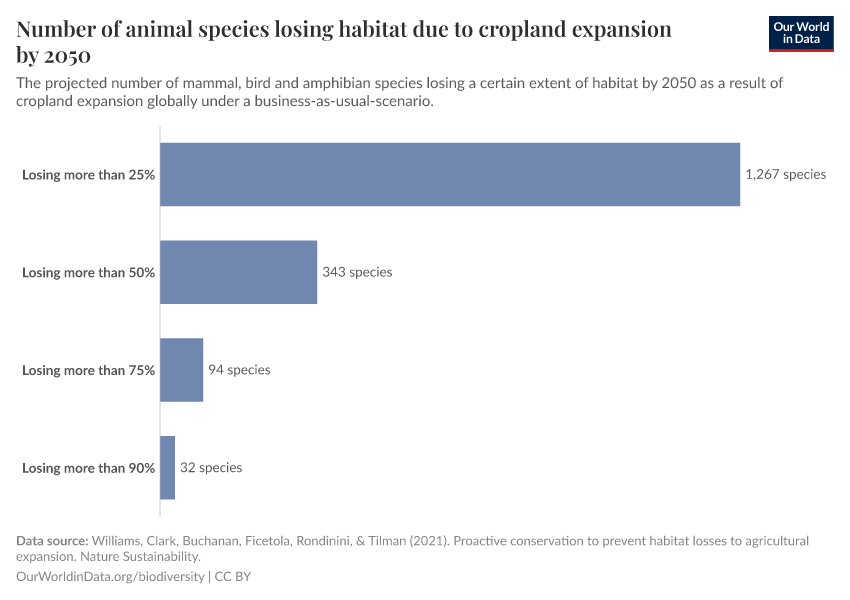

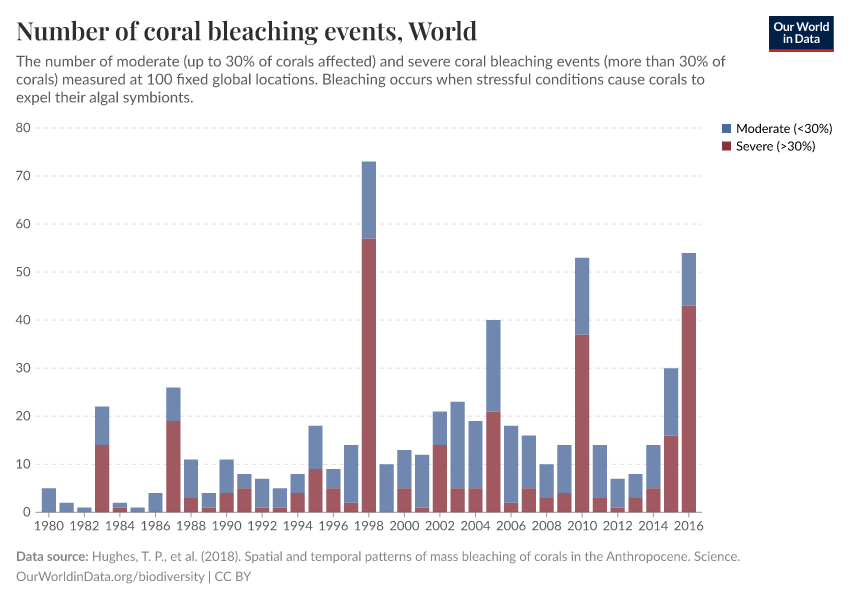

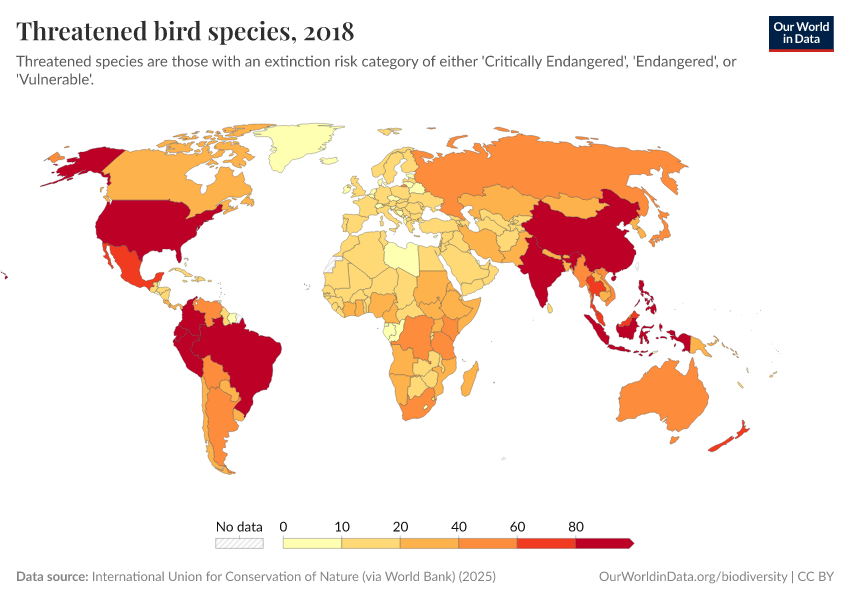

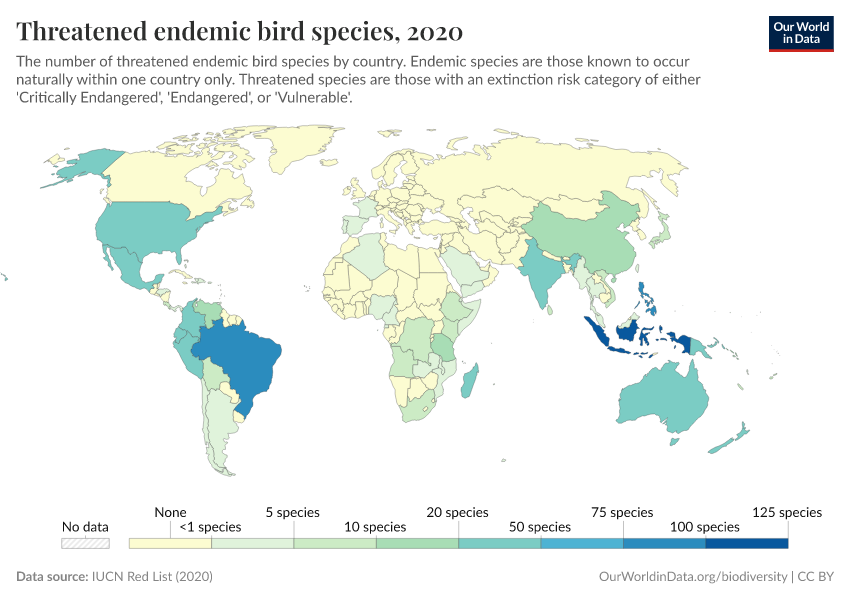

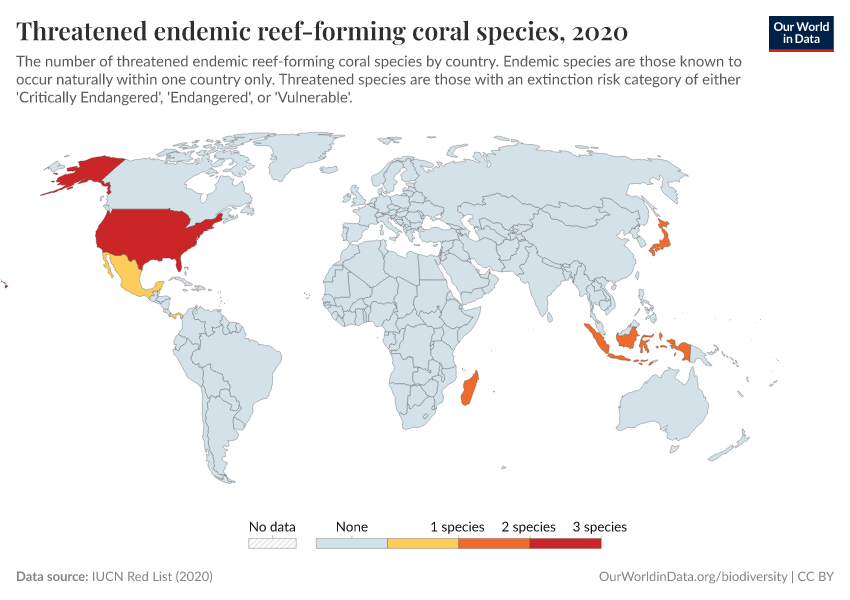

But we are just one of many species on Earth, and our demand for resources – land, water, food, and shelter – shapes the environment for other wildlife too.

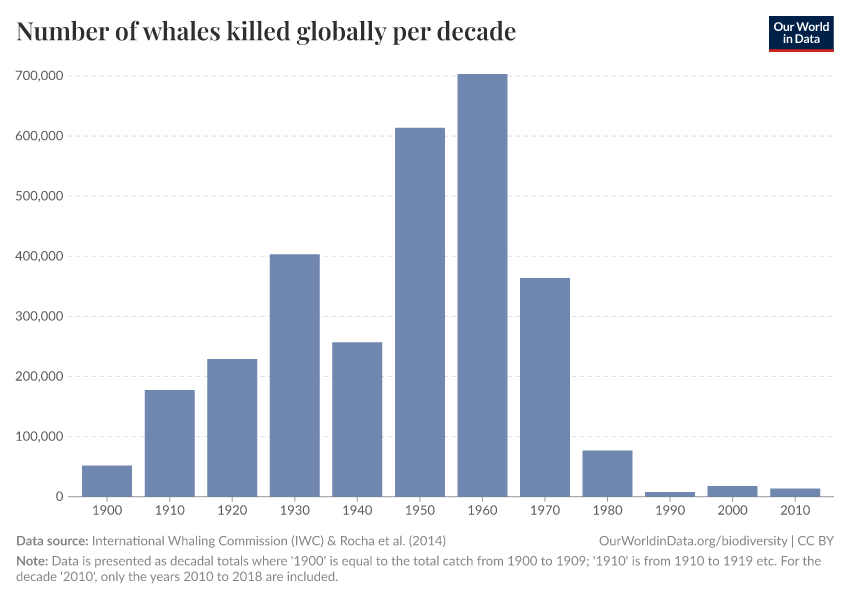

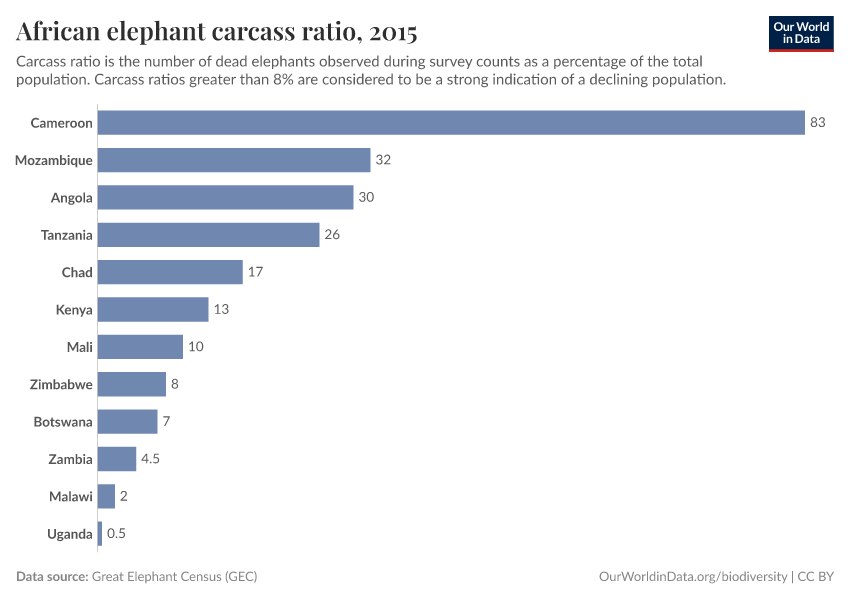

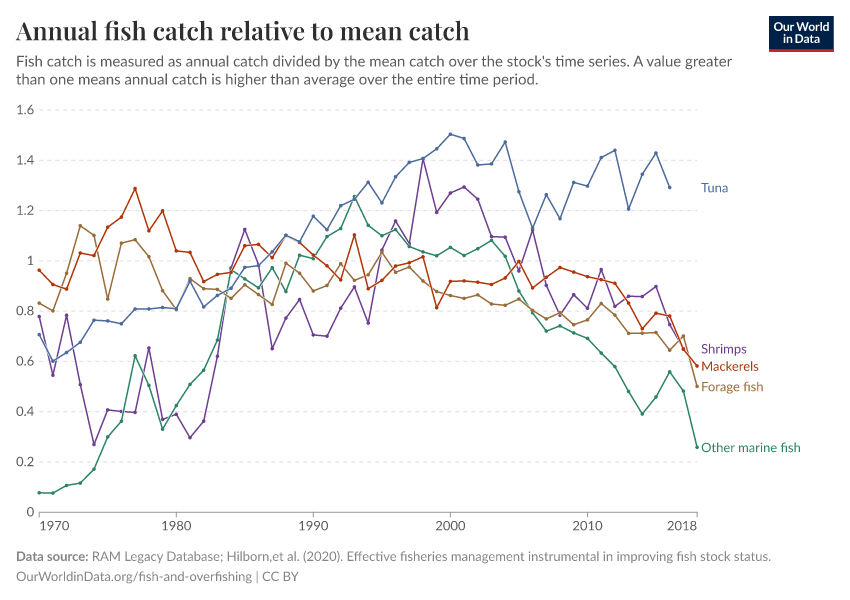

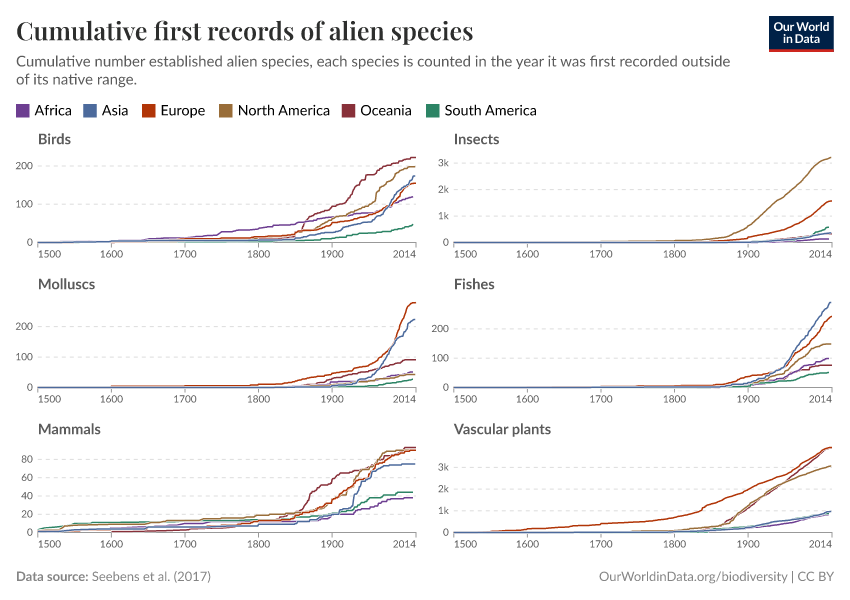

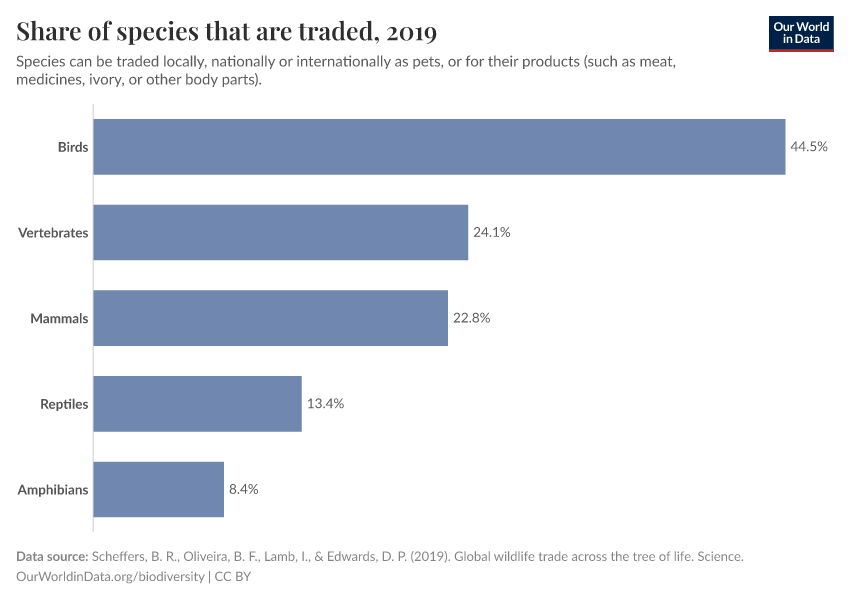

For millennia, humans have been reshaping ecosystems, directly through competition and hunting of other animals, and indirectly through deforestation and land use changes for agriculture.

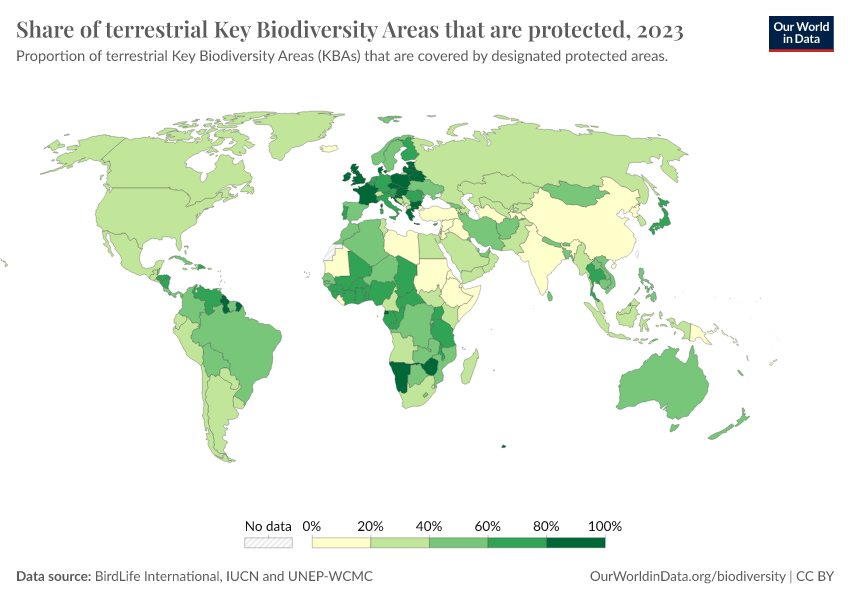

You can find all our data, visualizations, and writing related to biodiversity on this page. It aims to provide context on how biodiversity has changed in the past; the state of wildlife today; and how we can use this knowledge to build a future path where humans and other species can thrive on our shared planet.

Research & Writing

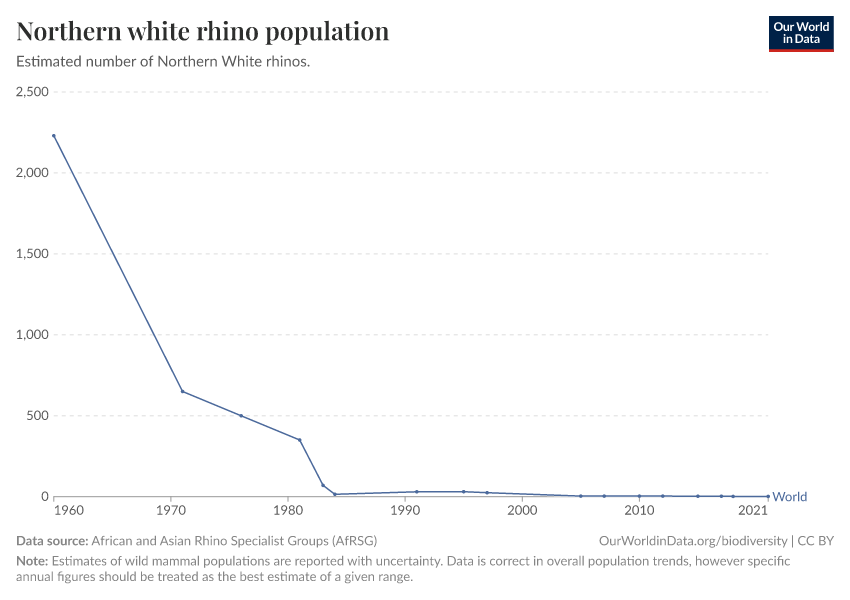

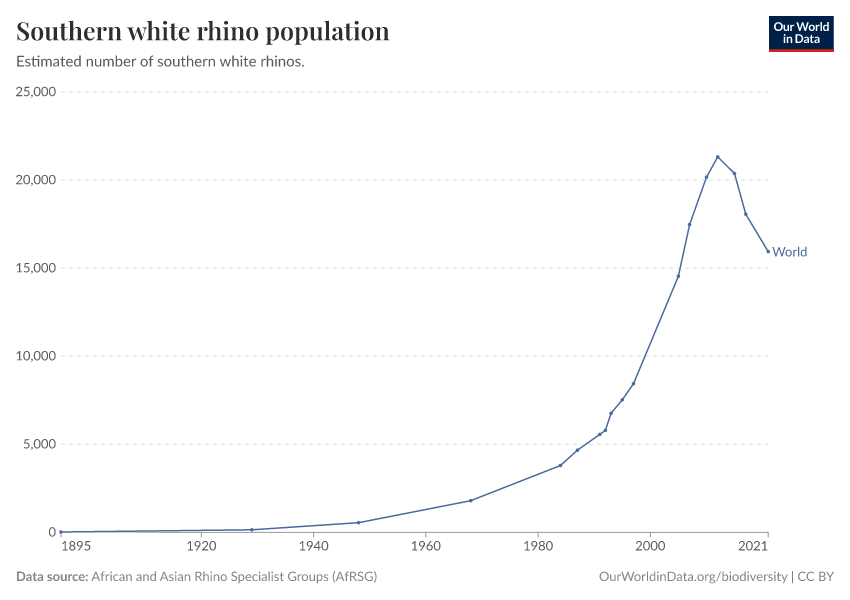

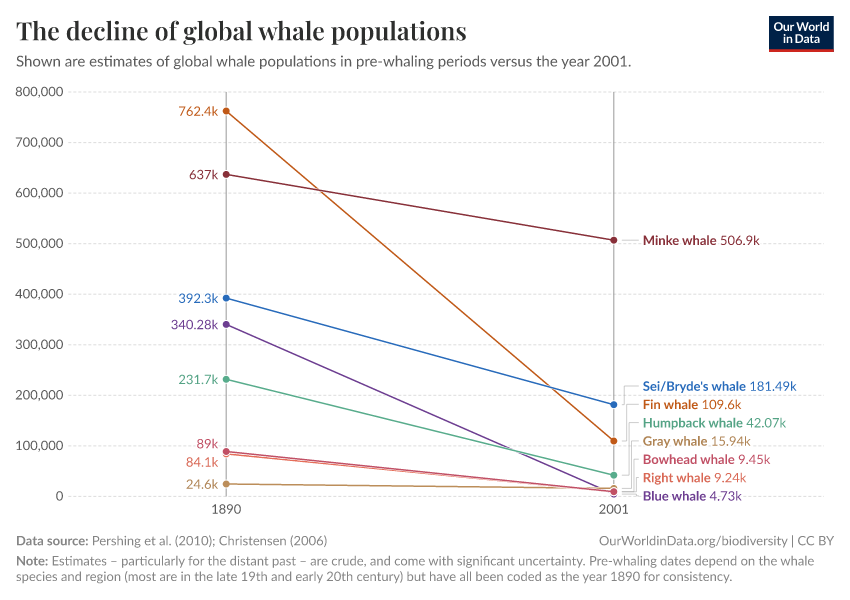

Wild mammals have declined by 85% since the rise of humans, but there is a possible future where they flourish

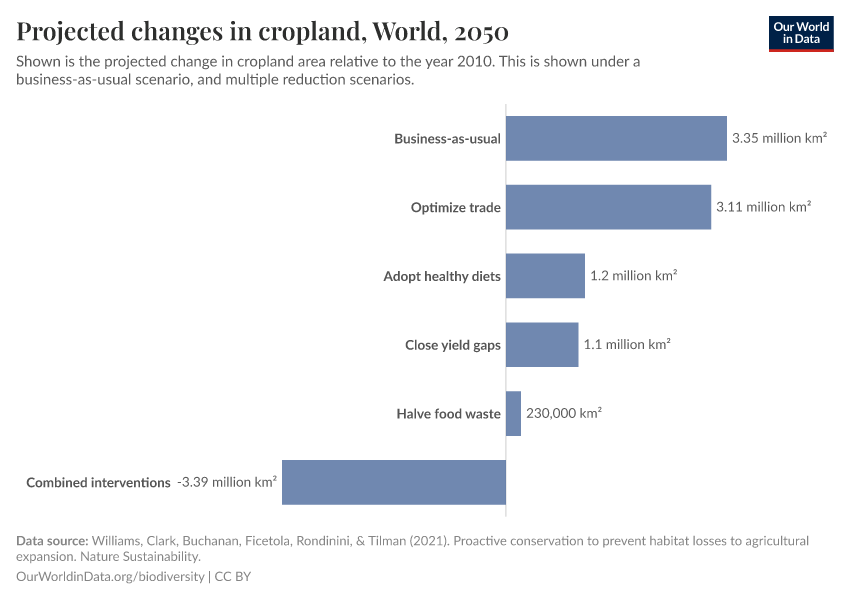

Wild mammal biomass has declined by 85% since the rise of humans. But we can turn things around by reducing the amount of land we use for agriculture.

Wild mammals are making a comeback in Europe thanks to conservation efforts

Hunting and habitat loss drove many large mammals in Europe close to extinction. New data shows us that many of the continent’s mammal populations are flourishing again.

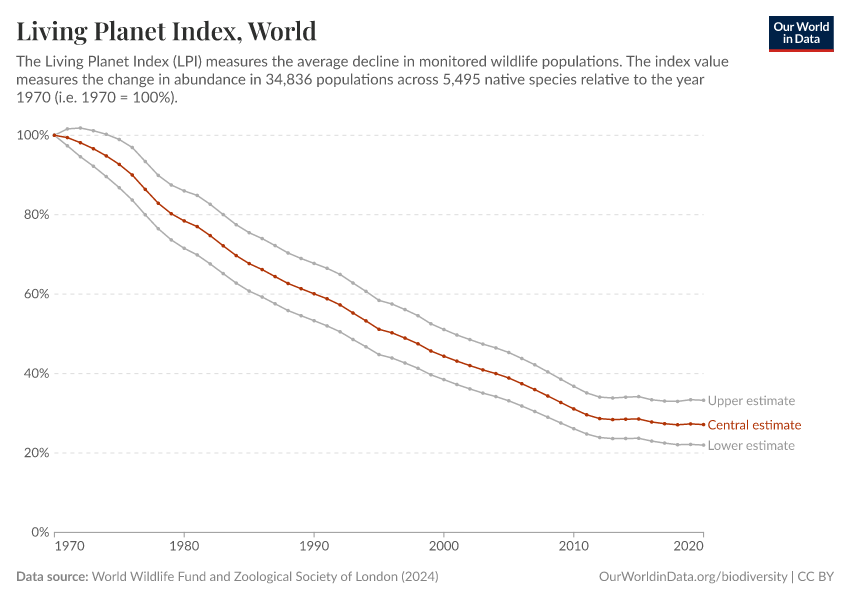

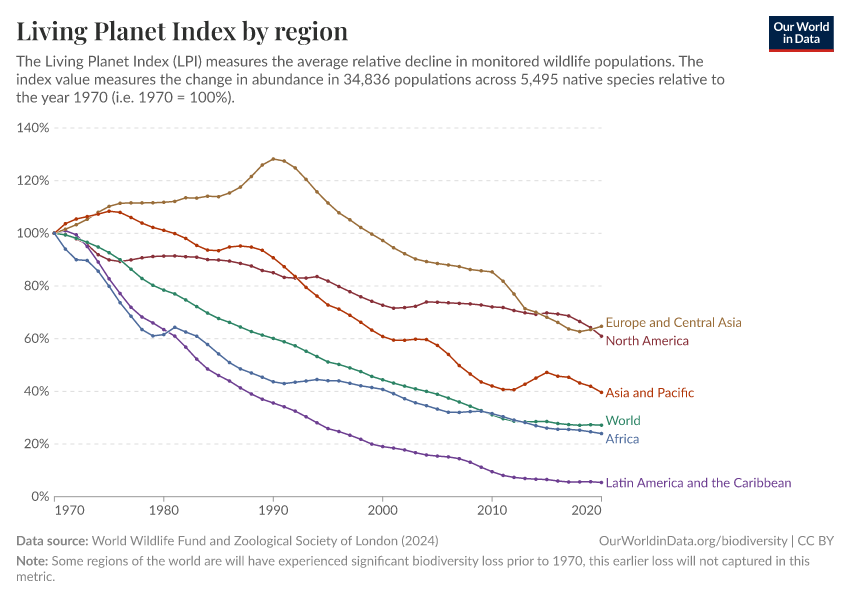

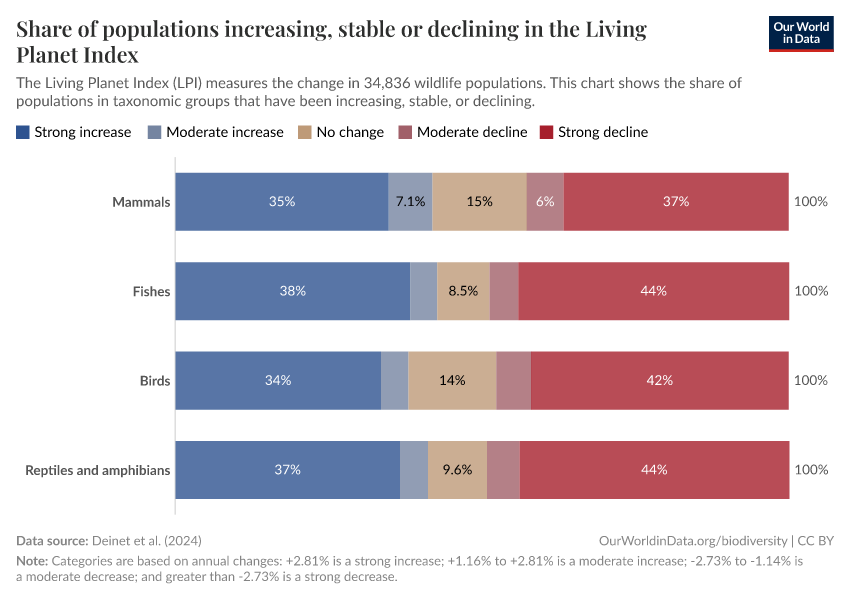

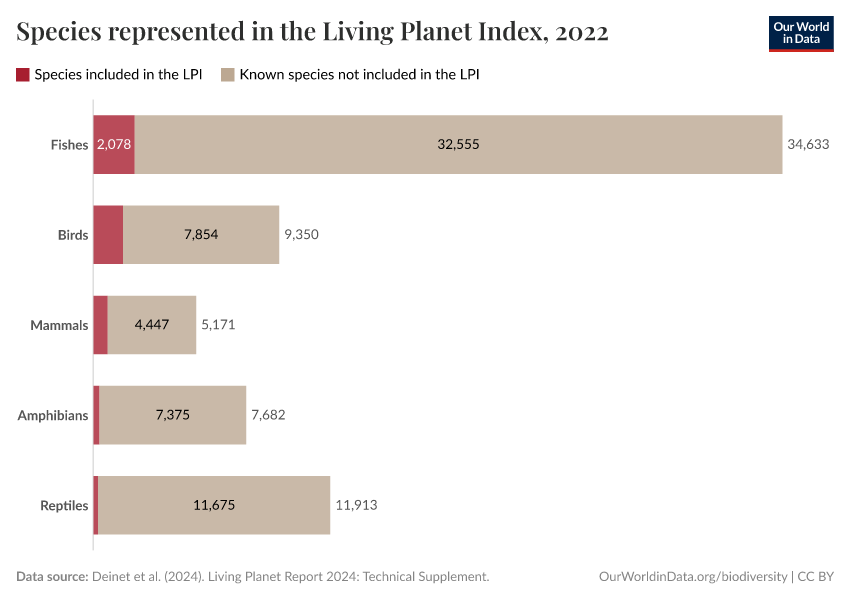

Living Planet Index

The 2024 Living Planet Index reports a 73% average decline in wildlife populations — what’s changed since the last report?

Living Planet Index: what does it really mean?

How the Living Planet project helps us understand how the world’s wildlife is changing

How did the Living Planet Index change in different world regions?

FAQs on the Living Planet Index

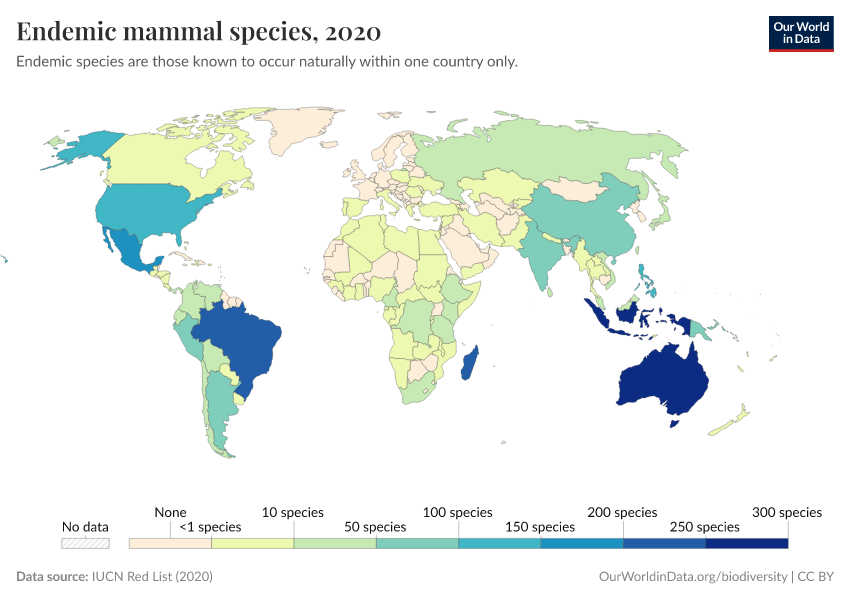

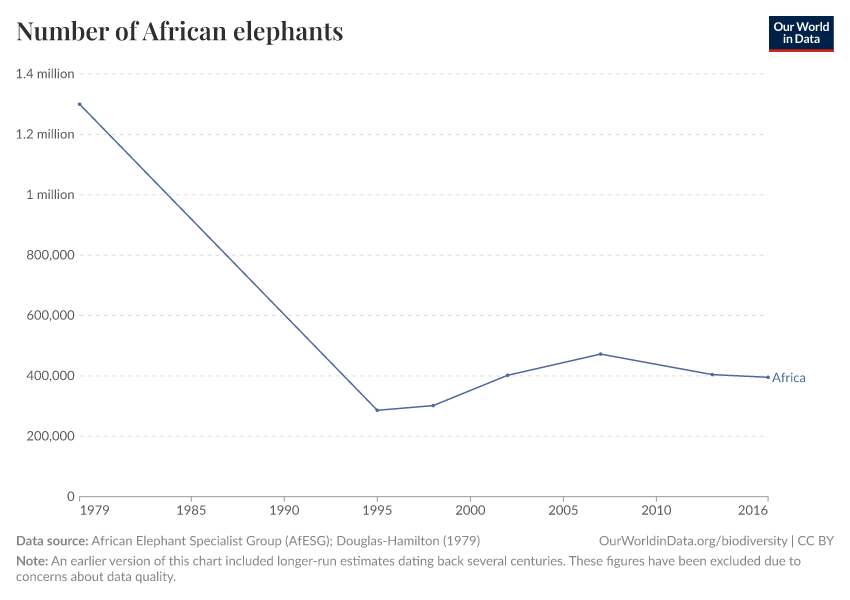

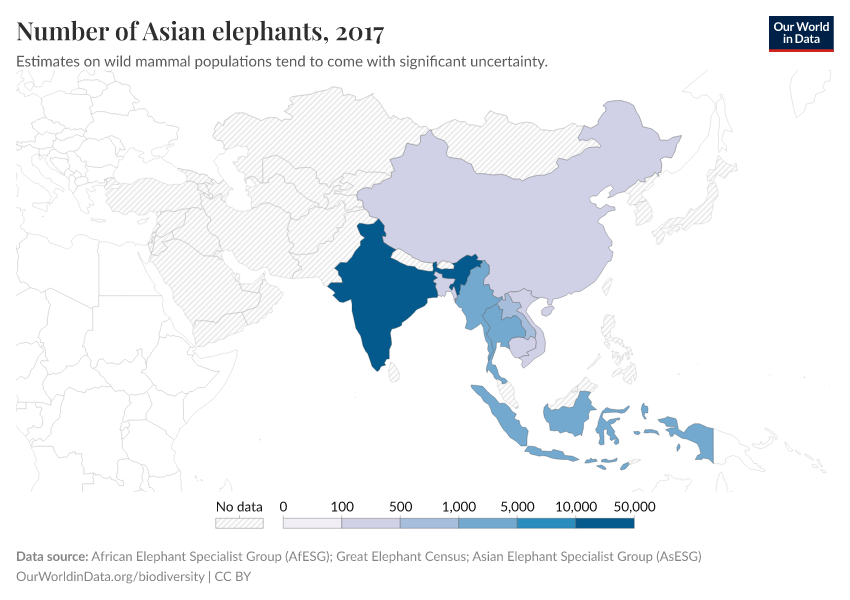

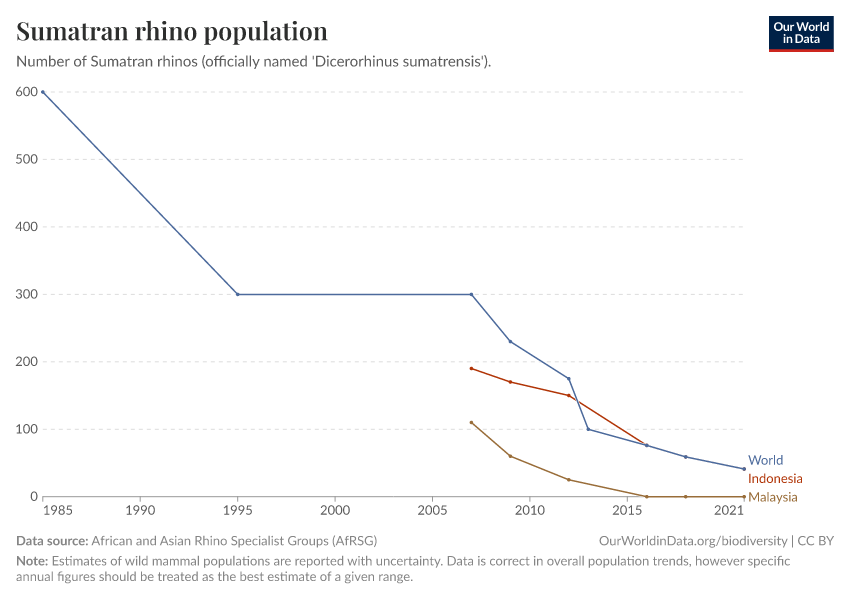

Mammals

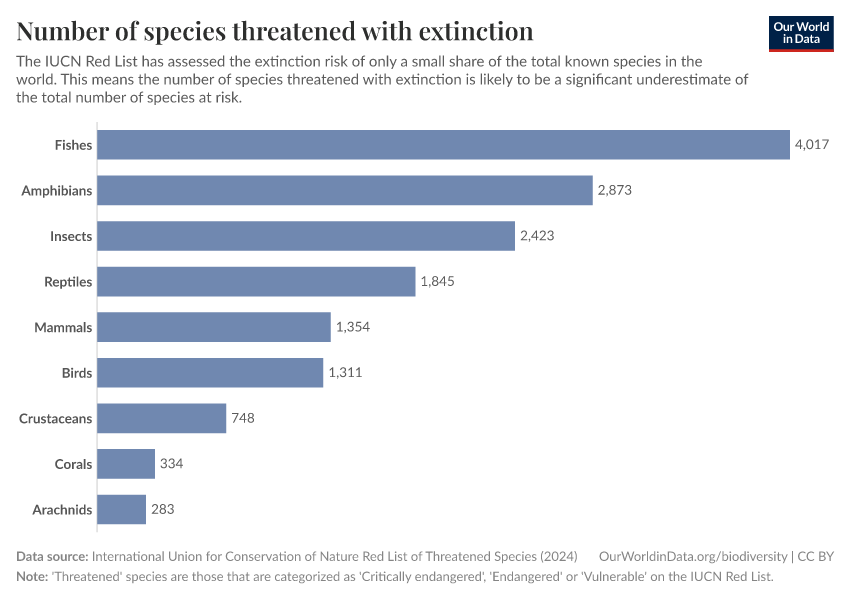

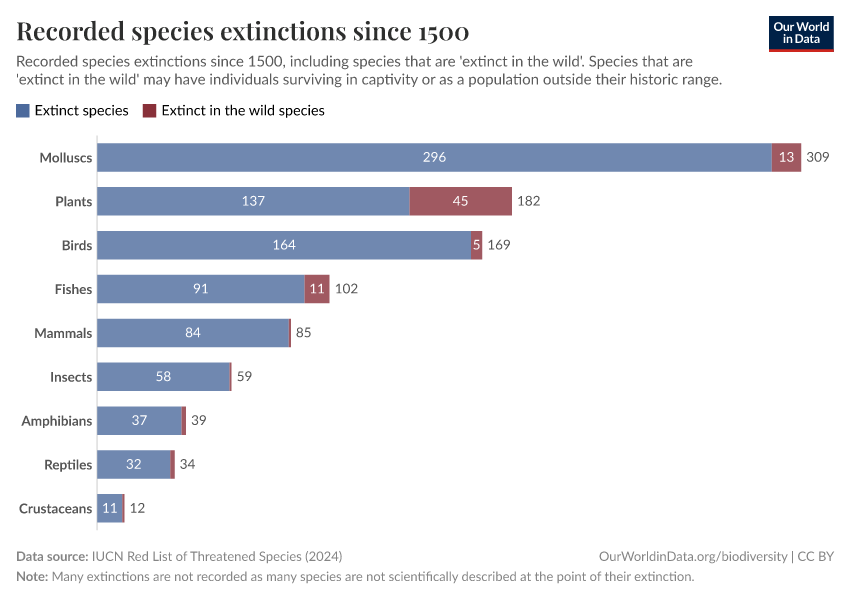

Extinctions

Other articles on Biodiversity

How much of the world’s food production is dependent on pollinators?

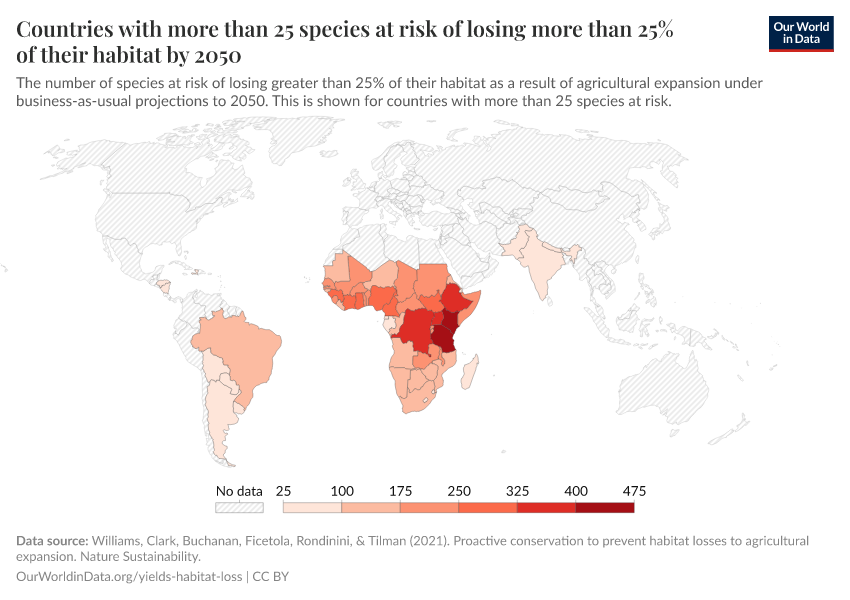

To protect the world’s wildlife we must improve crop yields – especially across Africa

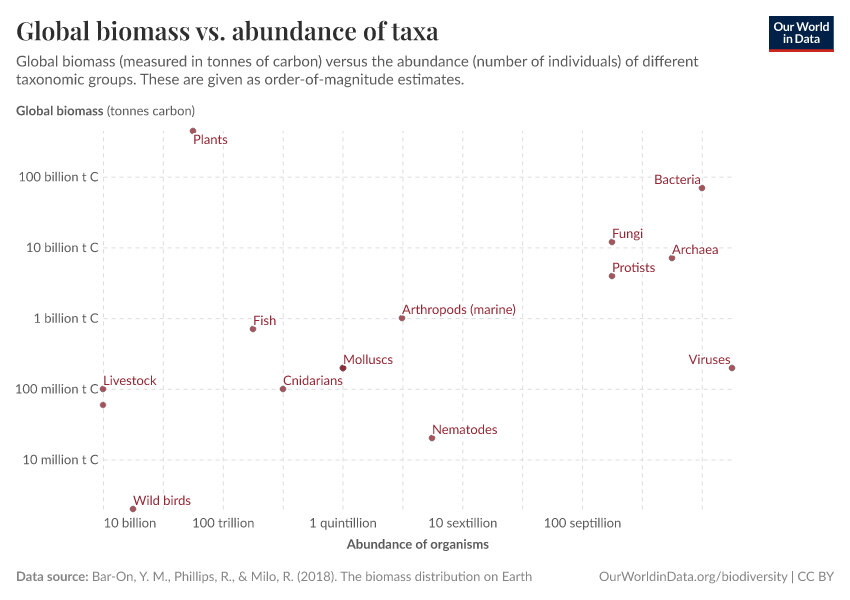

Humans make up just 0.01% of Earth’s life – what’s the rest?

Oceans, land, and deep subsurface: how is life distributed across environments?

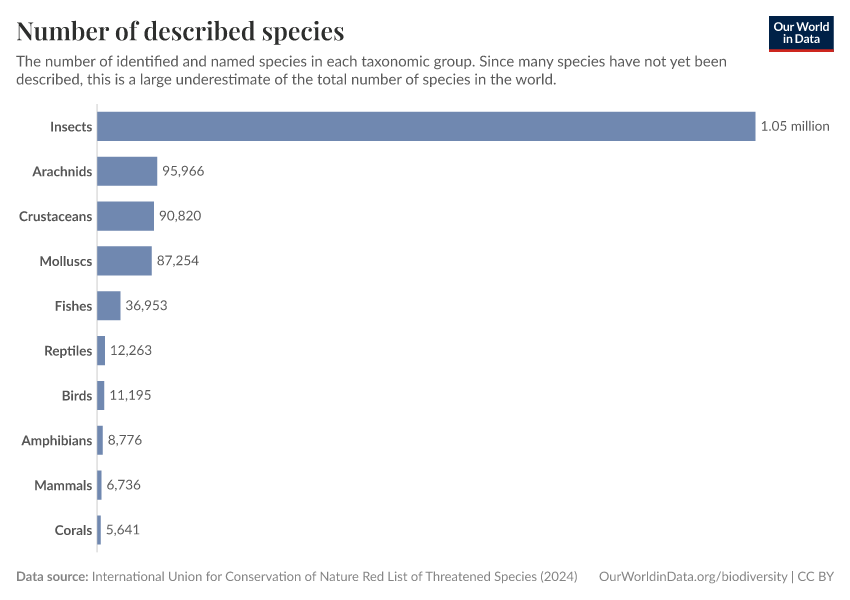

How many species are there?

Key Charts on Biodiversity

See all charts on this topicEndnotes

WWF (2024) Living Planet Report 2024 – A System in Peril. WWF, Gland, Switzerland.

Leung, B., Hargreaves, A. L., Greenberg, D. A., McGill, B., Dornelas, M., & Freeman, R. (2020). Clustered versus catastrophic global vertebrate declines. Nature, 588(7837), 267-271.

Bar-On, Y. M., Phillips, R., & Milo, R. (2018). The biomass distribution on Earth. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 115(25), 6506-6511.

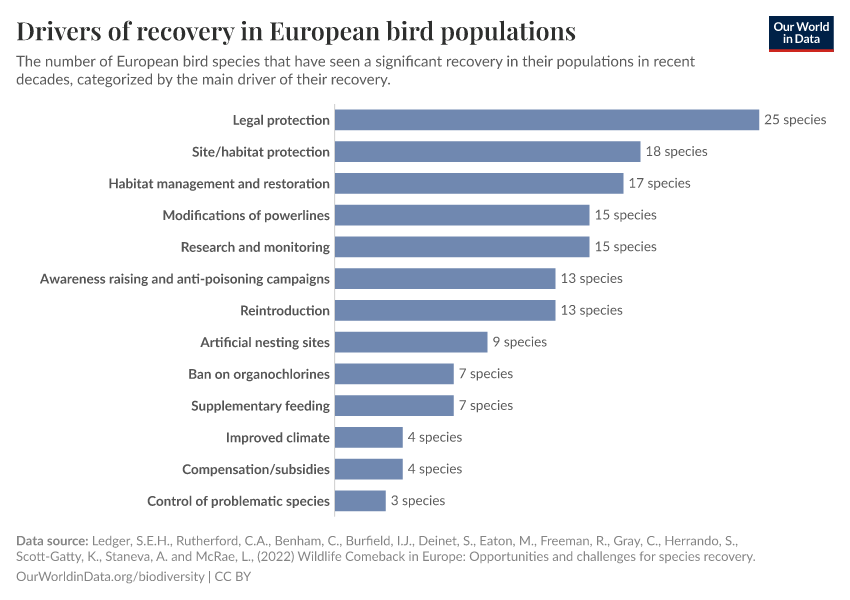

Ledger, S.E.H., Rutherford, C.A., Benham, C., Burfield, I.J., Deinet, S., Eaton, M., Freeman, R., Gray C., Herrando, S., Puleston, H., Scott-Gatty, K., Staneva, A. and McRae, L. (2022) Wildlife Comeback in Europe: Opportunities and challenges for species recovery. Final report to Rewilding Europe by the Zoological Society of London, BirdLife International and the European Bird Census Council.

Cite this work

Our articles and data visualizations rely on work from many different people and organizations. When citing this topic page, please also cite the underlying data sources. This topic page can be cited as:

Hannah Ritchie, Fiona Spooner, and Max Roser (2022) - “Biodiversity” Published online at OurWorldinData.org. Retrieved from: 'https://ourworldindata.org/biodiversity' [Online Resource]BibTeX citation

@article{owid-biodiversity,

author = {Hannah Ritchie and Fiona Spooner and Max Roser},

title = {Biodiversity},

journal = {Our World in Data},

year = {2022},

note = {https://ourworldindata.org/biodiversity}

}Reuse this work freely

All visualizations, data, and code produced by Our World in Data are completely open access under the Creative Commons BY license. You have the permission to use, distribute, and reproduce these in any medium, provided the source and authors are credited.

The data produced by third parties and made available by Our World in Data is subject to the license terms from the original third-party authors. We will always indicate the original source of the data in our documentation, so you should always check the license of any such third-party data before use and redistribution.

All of our charts can be embedded in any site.