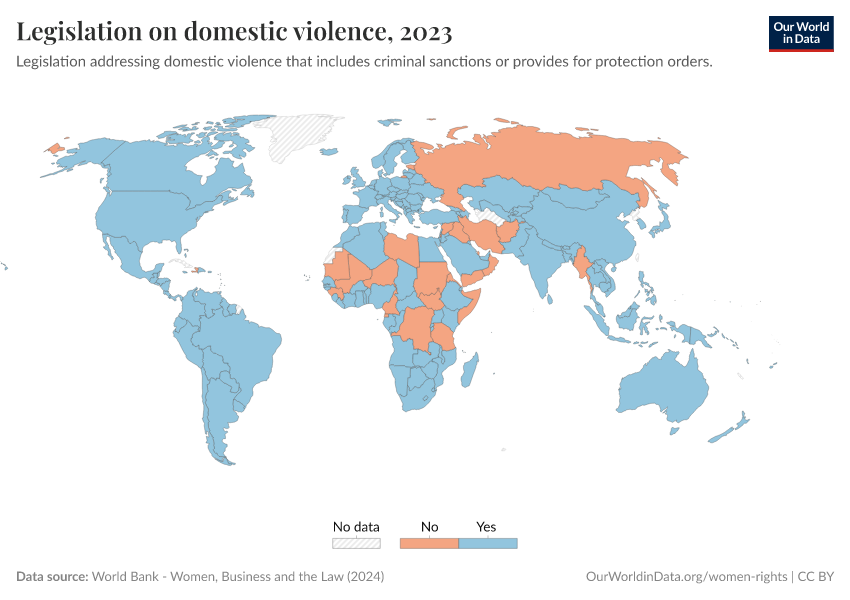

Legislation on domestic violence

What you should know about this indicator

- Domestic violence includes physical, sexual, psychological, and economic abuse in families or intimate relationships.

- The indicator measures whether legislation specifically addresses domestic violence.

- The answer is "yes" if the law explicitly covers all forms of domestic violence, includes criminal sanctions or protection orders, and criminalizes marital rape or allows a wife to file a complaint.

- The answer is "no" if there is no such legislation, if the law omits one or more forms of domestic violence, lacks sanctions or protection orders, protects only certain women or family members, does not criminalize marital rape, or only increases penalties for general crimes when committed within families.

- In the absence of such laws, survivors usually have only limited protection under general criminal law.

- Having a law does not mean it is enforced or effective in practice.

- This indicator uses standardized assumptions, like the woman having one child and residing in the largest business city, to ensure comparability, though this approach may not capture variations in laws affecting women in different states, rural areas, or minority groups.

What you should know about this indicator

- Domestic violence includes physical, sexual, psychological, and economic abuse in families or intimate relationships.

- The indicator measures whether legislation specifically addresses domestic violence.

- The answer is "yes" if the law explicitly covers all forms of domestic violence, includes criminal sanctions or protection orders, and criminalizes marital rape or allows a wife to file a complaint.

- The answer is "no" if there is no such legislation, if the law omits one or more forms of domestic violence, lacks sanctions or protection orders, protects only certain women or family members, does not criminalize marital rape, or only increases penalties for general crimes when committed within families.

- In the absence of such laws, survivors usually have only limited protection under general criminal law.

- Having a law does not mean it is enforced or effective in practice.

- This indicator uses standardized assumptions, like the woman having one child and residing in the largest business city, to ensure comparability, though this approach may not capture variations in laws affecting women in different states, rural areas, or minority groups.

Sources and processing

This data is based on the following sources

How we process data at Our World in Data

All data and visualizations on Our World in Data rely on data sourced from one or several original data providers. Preparing this original data involves several processing steps. Depending on the data, this can include standardizing country names and world region definitions, converting units, calculating derived indicators such as per capita measures, as well as adding or adapting metadata such as the name or the description given to an indicator.

At the link below you can find a detailed description of the structure of our data pipeline, including links to all the code used to prepare data across Our World in Data.

Reuse this work

- All data produced by third-party providers and made available by Our World in Data are subject to the license terms from the original providers. Our work would not be possible without the data providers we rely on, so we ask you to always cite them appropriately (see below). This is crucial to allow data providers to continue doing their work, enhancing, maintaining and updating valuable data.

- All data, visualizations, and code produced by Our World in Data are completely open access under the Creative Commons BY license. You have the permission to use, distribute, and reproduce these in any medium, provided the source and authors are credited.

Citations

How to cite this page

To cite this page overall, including any descriptions, FAQs or explanations of the data authored by Our World in Data, please use the following citation:

“Data Page: Legislation on domestic violence”, part of the following publication: Bastian Herre, Veronika Samborska, Pablo Arriagada, and Hannah Ritchie (2023) - “Women’s Rights”. Data adapted from World Bank Gender Statistics. Retrieved from https://archive.ourworldindata.org/20250916-204433/grapher/legislation-domestic-violence.html [online resource] (archived on September 16, 2025).How to cite this data

In-line citationIf you have limited space (e.g. in data visualizations), you can use this abbreviated in-line citation:

Women, Business and the Law; World Bank – processed by Our World in DataFull citation

Women, Business and the Law; World Bank – processed by Our World in Data. “Legislation on domestic violence” [dataset]. World Bank Gender Statistics, “World Bank Gender Statistics” [original data]. Retrieved January 3, 2026 from https://archive.ourworldindata.org/20250916-204433/grapher/legislation-domestic-violence.html (archived on September 16, 2025).