$3 a day: A new poverty line has shifted the World Bank’s data on extreme poverty. What changed, and why?

In June 2025, the World Bank increased its extreme poverty estimates by 125 million people. This doesn’t mean the world has gotten poorer: it reflects a new, higher International Poverty Line of $3 a day, up from $2.15.

To track progress towards ending extreme poverty by 2030, the United Nations relies on the World Bank to estimate the share of people living below a certain threshold, called the International Poverty Line (IPL).

In June 2025, the World Bank announced a major change to this line, raising it significantly, from $2.15 to $3 per day.

This increase partly reflects inflation — a consequence of the World Bank using international dollars at 2021 prices, updated from 2017 prices.

However, the IPL has also increased substantially, even after inflation adjustments. The poverty line has increased in real terms. And with it, so have the World Bank’s estimates of extreme poverty. 125 million people who would not have been counted as extremely poor before June are now included.1

This recent rise in the IPL is due to an aspect of the World Bank’s approach that some users of the data may not be aware of. Although it’s an international threshold, it is set to reflect national definitions of poverty typical among low-income countries. Several low-income countries recently raised their own poverty lines, pushing up the IPL.

The higher estimates of extreme poverty reflect a higher poverty threshold, not that the world is poorer. The updated data on global incomes accompanying the new IPL shows that incomes among the world’s poorest are higher than previously estimated.

Higher incomes but higher extreme poverty — this apparent paradox is unpacked in this article. We’ll explain in more detail how the International Poverty Line is defined, what has changed in the latest World Bank data, and what this means for our understanding of global poverty.

How the World Bank measures global extreme poverty

To understand the new data and what it tells us about global poverty, we must understand how the International Poverty Line is set and used.2

Estimating global extreme poverty involves two parts, illustrated in this figure and discussed in more detail below.

First, the World Bank estimates the global distribution of income (shown on the left) — that’s an estimate of how many people are living at each income level, summed across all countries.

Second, it defines an extreme poverty threshold, the International Poverty Line (shown on the right).

Together, these yield the World Bank’s estimates of extreme poverty: the share of the world’s population with incomes falling below the International Poverty Line.

Thinking separately about these two halves helps explain the paradox of the June 2025 update. As we’ll see, both sides of the calculation have changed simultaneously.

How the World Bank estimates the global income distribution

First, we’ll look at the left side of the calculation. You can think of the World Bank’s approach to estimating global incomes as being broken into three steps:

1) Collecting the raw ingredient: data from household surveys

The main way statisticians find out about people’s incomes is by asking them. Almost all countries run household surveys to gather this information. This is what the World Bank’s global data relies on.

Household surveys are run nationally, and their results can’t be directly compared at first. Countries ask different questions, capturing somewhat different definitions of income — as discussed in this footnote.3 Coverage also varies, with some countries conducting surveys annually, and others at intervals of several years. The survey data are also measured in different local currencies: households in India report in rupees, while households in Argentina report in pesos.

2) Estimating comparable national distributions

To get a global perspective on incomes, the World Bank takes a series of steps to make this national survey data as comparable as possible.4 One important step is converting the local currency data into international dollars. This hypothetical currency adjusts for differences in the cost of living between countries.

You can read more about this step in our dedicated article:

What is important to know here is that this conversion is based on “purchasing power parity” rates (PPPs) — a measure of how much local currency you need in each country to buy the same value of goods and services. PPPs are based on detailed price data collected in “rounds” every few years. The World Bank updated to a new round — the 2021 PPPs — which triggered them to revise the International Poverty Line.

With this harmonized survey data, the World Bank can estimate national distributions that allow incomes to be compared within and between countries worldwide.

3) Lining up the data to a common year

The available country data refers to a mix of different years and, in some cases, can be several years out of date. To account for how incomes may have changed, the World Bank “lines up” each country’s distribution to a reference year using growth rates observed in national accounts data.5

The lined-up, comparable national distributions can then be summed up to calculate the global income distribution for a given year.

How the World Bank sets the International Poverty Line

The other half of the World Bank’s approach to measuring extreme poverty is setting an International Poverty Line. Again, we can split this into three steps:

1) Collecting a comparable set of national poverty lines

The World Bank begins by collecting a large set of national poverty lines — the lines used by individual countries to estimate official poverty rates among their populations.

Like the income data, national poverty definitions can’t be meaningfully compared at first. The World Bank has developed an approach to align these, which you can learn more about in this footnote.6 The outcome is a comparable set of national poverty lines, all measured in international dollars.

2) Selecting the poverty lines in low-income countries

Making national poverty lines comparable shows us a clear pattern: richer countries generally set higher poverty lines.

The world’s poorest countries set very low national poverty lines — sometimes, as low as $1.50 per day. Among the world’s richest countries, poverty lines are much higher, at $30 or $40 per day.7

The International Poverty Line aims to be an extremely low income threshold, focusing the world’s attention on the situation of the poorest. To do this, the World Bank anchors the IPL to the national poverty lines adopted by low-income countries.

Countries are classified as “low-income” according to a technical classification system used across the World Bank’s work. We explain this in more detail in a dedicated article:8

3) Setting the IPL to the median poverty line among low-income countries

The IPL aims to reflect the typical definition of poverty adopted among low-income countries. For this, the World Bank uses the median value.

National poverty lines among low-income countries range from around $1.50 to $5 per day. When setting the IPL, the World Bank found the median poverty line among the 23 countries with available data to be $3.04, which was rounded to give $3 — the new value of the International Poverty Line.9

Once set, the International Poverty Line is applied to the global income distribution to estimate the share of people living in extreme poverty.

In the updated World Bank data, extreme poverty is higher, but so are global incomes

The summary of the World Bank’s approach above helps us understand the June 2025 update. Three statements summarize what has changed in the new data.

1) Inflation explains part of the rise

Even if nothing else had changed, the switch from 2017 to 2021 international-$ would have led to higher values — for both global incomes and the International Poverty Line.

As we explain in our article on international dollars, the value, or “purchasing power” of one international-$ is benchmarked to what one US dollar can buy in the United States. Prices in the US rose on average between 2017 and 2021 — about 11% in total.10 This means that one 2021 international dollar (the World Bank’s new units) is worth less than one 2017 international dollar (the old units). You need more 2021 international-$ to buy the same amount of goods and services.

We’ll look at how incomes and the IPL have changed before and after the June 2025 update. But here, we first plot this inflation as a backdrop to put those changes in context. To have stayed the same and kept the same purchasing power, global incomes and the IPL would have had to increase by 11% in nominal terms. That is shown in green in the chart. An increase beyond this level, falling in the beige area above, indicates a rise in real terms (an increase in the quantity or quality of goods and services it could buy).

2) The new data shows the world’s poorest are slightly better off

As part of the update, the World Bank has changed its estimates of global incomes. In the new data, incomes among the world’s poorest are higher.

This can be seen in the chart. The three arrows show how estimated incomes have changed before and after the update, across richer and poorer households. They show the percentage change in the “nominal” figures — without any inflation adjustment to account for the data having shifted from being measured in international-$ in 2017 prices to international-$ in 2021 prices.

The arrow on the left shows the change in the income level that places someone in the world’s poorest tenth in 2024. This rose by 28% in nominal terms, from $2.34 per day (measured in 2017 international-$) to $3.00 per day (in 2021 international-$).

Comparing this change to the green background, we see that incomes among the world’s poorest are higher not just because of inflation, but beyond inflation. They are higher in real terms. According to the new data, those at the bottom 10% of the global distribution can buy and consume more — 16% more — than the old data showed.11

The two other arrows show the nominal change at the global median and the top 10%. In contrast with incomes at the bottom 10%, these rose roughly in line with inflation: the data before and after the update agree about what households positioned here in the global distribution can afford.12 You can compare the data before and after the update in this chart.

This increase in incomes among the world’s poorest is due to two factors: new survey data and new price data.

With the update, the World Bank has added several new household surveys to its dataset. In particular, new data for India plays a big role. An improvement in the survey methodology used in India has shown incomes to be substantially higher than data based on earlier methods.13

Incomes at the bottom of the global distribution are also higher due to the change from 2017 to 2021 international dollars. As mentioned, these units use cross-country price data to adjust for differences in the cost of living. The new 2021 price data revises our picture of living standards in low-income countries, showing, on average, lower costs of living and consequently higher incomes.14

3) The International Poverty Line increased even more

The International Poverty Line rose by 40%, from $2.15 to $3, far beyond inflation and income growth.

Had the IPL only risen in line with inflation — an 11% increase from $2.15 to $2.38 — the World Bank’s new data on global incomes would show roughly 540 million people living in extreme poverty in 2024. That’s around a fifth lower than the World Bank’s estimates before the update — the effect of the higher incomes just discussed.

With the revised IPL, extreme poverty estimates for 2024 stand at 817 million — around 50% higher than had the IPL maintained its purchasing power and only risen in line with inflation. The calculations behind these numbers are given in the footnote here.15

This large real-terms rise in the IPL is the joint outcome of the many steps involved in setting the IPL, described above. In part, it reflects the use of the new 2021 PPPs and some changes in the group of countries classified as “low-income”.16 However, most of the increase is explained by changes in the raw ingredient: the national poverty lines on which the IPL is based.

Since the last revision of the International Poverty Line, several low-income countries have increased their poverty line substantially. This includes several countries with poverty lines falling close to the median value to which the IPL is anchored.17

As we saw, it’s common for countries to raise their poverty line as incomes increase. In the case of this group of countries, however, the step change is mostly a consequence of their adoption of an improved household survey methodology. For many of these countries, this resulted in higher recorded incomes, and national poverty lines were raised in line with this shift.18

Putting the updated International Poverty Line in context

Although it’s the result of a consistently applied methodology, the June 2025 update has seen a significant, real-terms jump in the International Poverty Line. This change has shifted the goalposts on the first, and best-known of the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals: the goal to eradicate extreme poverty by 2030. Around 125 million more people are now counted as living in extreme poverty under this new, higher threshold.

This increase does not mean that the world is poorer, though. According to the World Bank’s latest data, incomes among the world’s poorest are somewhat higher.

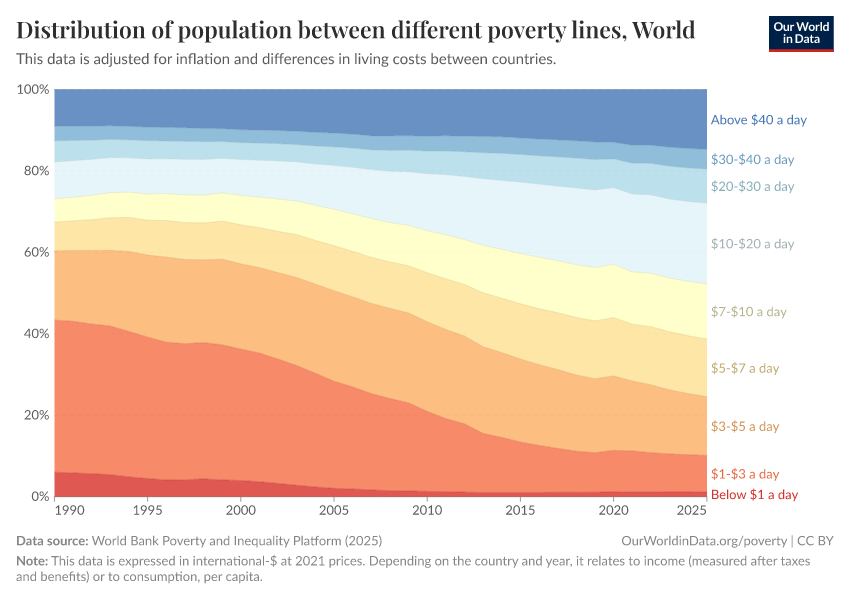

These revisions — to the IPL, the data on global incomes, and the estimates of extreme poverty they produce — are substantial. However, they need to be placed in context. This context is provided by the chart here, which shows the share of people living below a range of poverty thresholds since 1990.

Firstly, we must consider the recent revisions in the context of income changes over the past generation. The prevalence of extreme poverty decreased massively over this time, from one in every two or three people to one in ten. This is a huge change for our world. The revisions discussed in this article are small in the context of this large change over time.

They also need to be put in the context of the huge range of incomes we see globally today — the great inequality between rich and poor countries. Whether measured at $2.15 or $3, the International Poverty Line is an extremely low benchmark. In our home country, the United Kingdom, national poverty is measured using a threshold ten times higher than the IPL, close to $30 per day. This is similar to many other rich countries. As shown in the chart, if we apply this threshold globally, the vast majority — 80% — of the world’s population would be counted as poor.

Poverty, very clearly, does not end at the IPL. Although nine out of ten people today fall above this extreme definition of poverty, many of these people face living conditions that are barely imaginable for most people in rich countries: lacking access to clean water close to home; having to cook on solid fuel fires that create dangerous levels of indoor pollution; being unable to afford a diet that provides sufficient nutrients for themselves or their children. As global incomes grow, it’s right that we lift our ambitions about what should count as a morally acceptable minimum standard of living. From that perspective, the rise in the IPL can be seen as a positive step.

But at the same time, we also need to focus on the world’s poorest. This is crucial because of the huge number of people stuck on such extremely low incomes — perhaps the most important thing shown in the chart above. The progress seen in reducing extreme poverty over the past decades has ended. Incomes are stagnating in many countries where the world’s poorest live. Because of this, we are very clearly on track to fail in eradicating extreme poverty by 2030. That was clear in the data before the June 2025 update, and remains clear now.

Among the technical discussions needed to interpret the World Bank’s data correctly, we mustn’t lose sight of what this data shows: should current trends continue, hundreds of millions will remain in dire poverty for decades. That is surely one of the most important insights we could know about our world.

Acknowledgments

We thank Marwa Boukarim for her work designing and producing the article's visualizations and Max Roser, Edouard Mathieu, and Esteban Ortiz-Ospina for their valuable comments and feedback.

What are international dollars?

International dollars are used to compare incomes and purchasing power across countries and over time. Here, we explain how they’re calculated and why they’re used.

How does the World Bank classify countries by income?

The World Bank classifies countries into four income groups based on average income per person. This article explains how these groups are defined.

Beyond income: understanding poverty through the Multidimensional Poverty Index

The experience of poverty goes beyond a very low income. What is the Multidimensional Poverty Index, and how does it capture the diverse ways people experience deprivation?

Endnotes

According to the June 2025 update, 817 million people lived in extreme poverty in 2024 under the new $3 a day line. This is 125 million more than the previous estimate based on the old $2.15 definition. This chart compares the September 2024 data with the latest World Bank data.

This article discusses the World Bank’s current methodology. Although the general approach has remained relatively constant, the specifics have changed over time. For more background on the approach and its history, see the paper by World Bank researchers Dean Jolliffe and Espen Beer Prydz (2016). Estimating International Poverty Lines from Comparable National Thresholds. Policy Research Working Paper 7606. World Bank, Washington, D.C.

A particularly important difference concerns the use of income and consumption surveys. While the data for high-income countries measures households’ post-tax income, most low and middle-income countries measure the value of households’ consumption of goods and services. For convenience, in this article, we’ll use “income” to refer to what is, in reality, a mix of income and consumption data.

Although the World Bank takes many steps to harmonize the national survey data, this is one important difference it cannot adjust for.

Income and consumption are closely related but not the same: households' consumption equals their income minus any savings.

One important difference is that, while zero consumption is not a feasible value — people with zero consumption would starve — zero income is a possible value. This means that income and consumption can give quite different pictures of a person’s economic situation at the bottom end of the distribution. For instance, a person spending their savings in retirement may have a very low, or even zero, income, but have a high level of consumption nevertheless.

Therefore, income-based estimates of extreme poverty are generally higher than consumption-based estimates. Indeed, we see this in the data for several Eastern European countries that include data points for both measures.

This mixing of concepts is a limitation of the global “incomes” data more generally, but not a problem for the global estimates of extreme poverty, since almost all the world’s extreme poor live in countries with consumption surveys.

See the World Bank’s Poverty and Inequality Platform’s methodology documentation, Chapters 2 and 3, for more details.

National accounts are a set of statistics, produced by almost every country in the world, that aim to measure incomes, consumption, and production across the whole economy. The best known national accounts series is Gross Domestic Product (GDP) — a measure of the value of goods and services produced in a country (and the income this generates). However, the data also includes other series that capture other concepts. This includes Household Final Consumption Expenditure (HFCE) — the total value of goods and services purchased by households.

To line up the survey data to a common year, the World Bank uses the growth rates seen in either GDP or HFCE. It assumes that every person’s income in a country has increased (or decreased) at the same rate — i.e., that inequality stays the same as found in the most recent survey data.

For more information, see the World Bank’s methodology documentation, especially Chapter 5, available on the Poverty and Inequality Platform website.

As well as using different local currencies, national poverty definitions are often made up of a schedule of varying poverty lines — tailored to geographic regions or to account for various household sizes. The particular approach differs widely across countries, making direct comparisons impossible.

The World Bank relies on the harmonized income distribution data discussed above to create a comparable set of national poverty lines. For each country, it finds the income threshold that gives the same poverty rate as reported in official national estimates when applied to its distribution.

For example, the poverty line for Ethiopia included in the World Bank’s harmonized dataset is based on a 2015 household survey. The official national poverty rate in that year was 23.5%, based on a national poverty definition expressed in the local currency, Birr.

You can read more about that survey and how the poverty line was set in the national report analyzing the survey’s results, the 2016 Poverty Interim Report (available on Scribd and at the International Household Survey Network). This is summarized in the World Bank’s October 2024 ‘Poverty and Equity Brief’ for Ethiopia.

According to the World Bank’s harmonized “incomes” data, 23.5% of people consumed $2.59 per day or less in 2015 (measured in 2021 international dollars). Therefore, $2.59 per day is the comparable national poverty line used in the World Bank’s calculation of the IPL.

You can read more about the method in Foster et al. (2025) — the World Bank paper accompanying the June 2025 update to the IPL. An older paper, Jolliffe and Beer Prydz (2016), initially set out the methodology and provides a good background.

Foster, E.M., Jolliffe, D., Ibarra, G.L., Lakner, C., Tetteh Baah, S.K. (2025). Global Poverty Revisited Using 2021 PPPs and New Data on Consumption. Policy Research Working Paper 11137. World Bank, Washington, D.C.

Jolliffe, D., & Prydz, E. B. (2016). Estimating International Poverty Lines from Comparable National Thresholds. Policy Research Working Paper 7606. World Bank, Washington, D.C.

Here are some examples. Democratic Republic of Congo: $1.48; Uganda: $1.52; Madagascar: $1.77; France: $31.98; UK: $32.45; Germany: $39.23; Norway: $43.16 (all measured in 2021 international-$). You can see the harmonized national poverty lines for each country plotted against GDP per capita in this chart here.

It’s worth noting that this income group classification uses a different measure of income than the one we’ve just seen based on household survey data. It uses the “Atlas method”, which is based on National Accounts data without adjusting to account for differences in the cost of living across countries. Because of this, the rankings of countries differ somewhat between the two measures. Due to the harmonized survey data on which the World Bank’s poverty estimates are based, several countries defined as “low-income” actually have higher average incomes than some “lower-middle” income countries.

For more details of the calculation, see Foster et al. (2025). There, they also conduct a range of robustness checks showing that different aggregation methods lead to similar IPL values. However, they note that the poverty lines are more “bimodal” than at the last update, “with some low-income countries clustering at a lower poverty line of around $2.00 or a higher poverty line of around $3.40”.

Foster, E.M., Jolliffe, D., Ibarra, G.L., Lakner, C., Tetteh Baah, S.K. (2025). Global Poverty Revisited Using 2021 PPPs and New Data on Consumption. Policy Research Working Paper 11137. World Bank, Washington, D.C.

This figure for US inflation is taken from the World Bank paper accompanying the new IPL and measures the consumer price index.

Foster, E.M., Jolliffe, D., Ibarra, G.L., Lakner, C., Tetteh Baah, S.K. (2025). Global Poverty Revisited Using 2021 PPPs and New Data on Consumption. Policy Research Working Paper 11137. World Bank, Washington, D.C.

Figures refer to the data for 2024 before and after the June 2025 update. The nominal increase is $3.00 / $2.34 – 1 = 28%.

Updating the old value only for the 11% inflation seen in the US, in line with the value of the international-$ — yields a P10 of $2.60 ($2.34 x 1.11). The real terms increase in the global P10 is $3.00 / ($2.34 x 1.11) – 1 = 16%.

The median before the update was $8.25 (2017 int.-$) and $9.20 after (2021 int.-$). $9.20 / $8.25 – 1 = 12%. The threshold to the top 10% was $48.40 before and $53.70 after. $53.70 / $48.40 – 1 = 11%.

The survey data for India measures household consumption. (As discussed more in footnote 3, in this article, we are using “income” as a convenient shorthand for the mix of income and consumption survey data that goes into the World Bank’s estimates.)

India recently published the 2022–23 household survey — the first in over a decade. This survey uses a different recall period when asking people about their consumption of various goods. A shorter recall period is used for food and other frequently consumed items; a longer recall period is used for items purchased more infrequently. Previous surveys used a fixed recall period across all consumption categories. Studies have shown that the newer, “mixed reference period” approach captures a higher consumption. People can remember their consumption more accurately. The 2022–23 India survey also changed in other ways, such as the questionnaire, the number of visits, and the sample design.

The new survey data has increased the incomes for India shown in the World Bank not just for 2022-23 but for the entire series. To avoid a break in the series for such a populous country, the World Bank has adjusted the earlier data to be more comparable with the new data.

You can read more in the following World Bank papers:

Mahler, D.G., Foster, E., Tetteh-Baah, S., 2024. How Improved Household Surveys Influence National and International Poverty Rates. World Bank, Washington, D.C.

Foster, E.M., Jolliffe, D., Ibarra, G.L., Lakner, C., Tetteh Baah, S.K. (2025). Global Poverty Revisited Using 2021 PPPs and New Data on Consumption. Policy Research Working Paper 11137. World Bank, Washington, D.C.

World Bank (2025). India: Trends in Poverty, 2011-12 to 2022-23. Methodology Note. World Bank, Washington, D.C.

As shown in this chart, with the change from 2017 to 2021 international-$, there has generally been a larger increase in nominal incomes among low-income countries than in high-income countries — 21% compared to 11% on average (Foster et al. (2025), Table C1).

A nominal increase of 11% — in line with US inflation in this period — means that the income of high-income countries is, on average, the same in terms of purchasing power measured in either unit. There has been a greater increase among low-income countries, so they are, on average, slightly better off when incomes are calculated in the new 2021 international-$.

Foster, E.M., Jolliffe, D., Ibarra, G.L., Lakner, C., Tetteh Baah, S.K. (2025). Global Poverty Revisited Using 2021 PPPs and New Data on Consumption. Policy Research Working Paper 11137. World Bank, Washington, D.C.

As discussed in this article, the IPL would have had to increase in line with US inflation of 11% to maintain its purchasing power.

$2.15 * 1.11 = $2.386 (3.d.p.). This rounds to $2.39. In Foster et al. (2025), this inflation-adjusted IPL value is reported as $2.38. We assume the <$0.01 discrepancy is due to rounding of the US inflation figure.

The World Bank’s Poverty and Inequality Platform allows you to query the global distribution at $0.10 intervals. As of August 1, 2025, the data shows that 545 million people lived below $2.40 (2021 int-$) in 2024. The number living below $2.38 falls slightly below that, approximately 540 million.

Prior to the June 2025 update, the World Bank estimated that 692 million people would be living in extreme poverty in 2024. This estimate is based on older survey data, the 2017 PPPs, and the $2.15-a-day poverty line.

692 million minus 540 million is 152 million, or approximately 150 million. 152 / 692 = 22%, or roughly a fifth fewer people in extreme poverty.

Based on the new data, new PPPs, and $3 a day IPL, the estimate for 2024 is $817 million. 817 / 540 – 1 = 51%, or roughly half as many more people in extreme poverty.

Foster, E.M., Jolliffe, D., Ibarra, G.L., Lakner, C., Tetteh Baah, S.K. (2025). Global Poverty Revisited Using 2021 PPPs and New Data on Consumption. Policy Research Working Paper 11137. World Bank, Washington, D.C.

Adjusting only for inflation in the US (11%) would have taken the IPL to $2.38. Foster et al. (2025) show that accounting for both inflation and the change in relative prices brought in the PPP revision — but with no other changes — would have led to an IPL of $2.46 (a 14% increase).

Some countries, including Azerbaijan, Benin, Nepal, Uzbekistan, and Zimbabwe, have moved out of the “low-income” group since the last update to their poverty lines. However, because their old poverty lines were spread above and below the median, their exclusion had little impact on the final IPL value.

Note that the IPL is calculated using the World Bank’s income classification for each country in the year their poverty line was defined. So, although (for example) Azerbaijan was already classified as a lower-middle-income country when the previous $2.15 a day IPL was set, its poverty line dated back to 2001, when it was a low-income country. As such, it was included in the set from which the median is calculated to give the IPL.

Foster, E.M., Jolliffe, D., Ibarra, G.L., Lakner, C., Tetteh Baah, S.K. (2025). Global Poverty Revisited Using 2021 PPPs and New Data on Consumption. Policy Research Working Paper 11137. World Bank, Washington, D.C.

For example, Burkina Faso. When the World Bank set the $2.15 a day IPL, the national poverty line for the country was $2.16. In setting the $3-a-day IPL, the national poverty line moved to $3.04, a 41% increase in nominal terms (the former being measured in 2017 international-$, the latter 2021 international-$).

Other relevant countries include Central African Republic ($2.16 → $2.82; 31% increase), Chad ($2.66 → $3.42; 29% increase), Guinea-Bissau ($2.28 → $3.47; 52% increase), Mali ($1.95 → $3.41; 75% increase), Niger ($1.87 → $2.39; 28% increase), and Togo ($2.17 → $3.51; 62% increase).

Again, the surveys in question measure household consumption (see footnote 3 for a discussion of consumption vs income surveys). Through more detailed, comprehensive questionnaires, these surveys now do a better job of capturing what people consume, and have shown household consumption to be higher than previously found.

Like most low-income countries, the national poverty lines in these countries are set to reflect the cost of basic needs, incorporating both a food and a non-food component. These are set based on consumption patterns observed in household survey data: the non-food allowance reflects how households balance food and non-food needs. The revised survey methodology increased observed non-food consumption in a number of countries, which led them to set a higher non-food allowance within their cost-of-basic-needs poverty lines.

You can read more about this in this World Bank blog or the paper by Daniel Mahler and colleagues (2024).

Mahler, D.G., Foster, E., Tetteh-Baah, S., 2024. How Improved Household Surveys Influence National and International Poverty Rates. World Bank, Washington, D.C.

Cite this work

Our articles and data visualizations rely on work from many different people and organizations. When citing this article, please also cite the underlying data sources. This article can be cited as:

Joe Hasell, Bertha Rohenkohl, and Pablo Arriagada (2025) - “$3 a day: A new poverty line has shifted the World Bank’s data on extreme poverty. What changed, and why?” Published online at OurWorldinData.org. Retrieved from: 'https://archive.ourworldindata.org/20251125-173858/new-international-poverty-line-3-dollars-per-day.html' [Online Resource] (archived on November 25, 2025).BibTeX citation

@article{owid-new-international-poverty-line-3-dollars-per-day,

author = {Joe Hasell and Bertha Rohenkohl and Pablo Arriagada},

title = {$3 a day: A new poverty line has shifted the World Bank’s data on extreme poverty. What changed, and why?},

journal = {Our World in Data},

year = {2025},

note = {https://archive.ourworldindata.org/20251125-173858/new-international-poverty-line-3-dollars-per-day.html}

}Reuse this work freely

All visualizations, data, and code produced by Our World in Data are completely open access under the Creative Commons BY license. You have the permission to use, distribute, and reproduce these in any medium, provided the source and authors are credited.

The data produced by third parties and made available by Our World in Data is subject to the license terms from the original third-party authors. We will always indicate the original source of the data in our documentation, so you should always check the license of any such third-party data before use and redistribution.

All of our charts can be embedded in any site.