Plastic Pollution

Originally published in November 2023; substantially updated in February 2026.

Plastic production has sharply increased over the last 70 years. In 1950, the world produced just two million tonnes. It now produces over 450 million tonnes.

Plastic has added much value to our lives: it’s a cheap, versatile, and sterile material used in various applications, including construction, home appliances, medical instruments, and food packaging.

However, when plastic waste is mismanaged — not recycled, incinerated, or kept in sealed landfills — it becomes an environmental pollutant. In particular, one to two million tonnes of plastic enter our oceans yearly, affecting wildlife and ecosystems.

Improving the management of plastic waste across the world — especially in poorer countries, where most of the ocean plastics come from — is therefore critical to tackling this problem.

This page presents all of our data and writing on plastic pollution.

Plastic production has more than doubled in the last two decades

The first synthetic plastic — Bakelite — was produced in 1907, marking the beginning of the global plastics industry.

However, rapid growth in global plastic production didn’t happen until the 1950s. Over the next 70 years, however, the annual production of plastics has increased nearly 230-fold to 460 million tonnes in 2019.

Even just in the last two decades, global plastic production has doubled.

People in richer countries tend to use more plastic — and generate more plastic waste — than those in poorer countries, but plastic is now widely used across the world (and at all income levels).

Plastic pollution is mostly about how waste is managed, not how much is produced

Rich countries tend to produce more plastic waste per person. This is clear from the global data.

But if we’re concerned about the environmental impacts of plastics in terms of their ability to escape into the natural environment, enter rivers or oceans, harm wildlife, or generate harmful air pollution through burning, then what matters is plastic pollution. That is mismanaged plastic waste at risk of leaking into the environment.

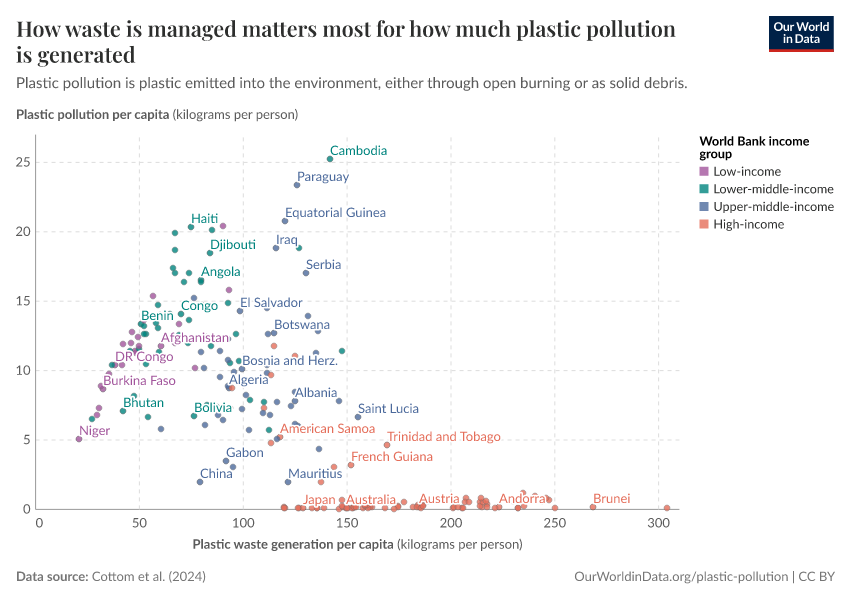

What we find is that the amount of plastic waste generated doesn’t tell us much about the amount of plastic pollution. You can see this clearly in this scatterplot. The horizontal axis shows the amount of plastic waste generated per person. The vertical axis shows how much plastic pollution is emitted per person — that is, plastic that is burned (causing toxic air pollution) or lost as debris, after which it can enter rivers, ecosystems, and the ocean.

High-income countries tend to generate much more plastic waste per person. The average American or Spaniard generates around four times as much as the average Indian, and ten times as much as an Ethiopian. But these high-waste producers do not leak much waste into the environment; their pollution is close to zero.

In contrast, the countries that generate the most plastic pollution often produce much less plastic waste per person. Poor waste management is the bigger problem, not how much plastic they use. When waste is not collected, safely disposed of, or properly treated, it becomes a pollutant and leaks into the environment.

Low- to middle-income countries tend to produce much more plastic pollution

The chart shows the average amount of plastic pollution generated per person among countries within each income group.

This includes both the open burning of plastics — which generates toxic air pollution — and the leakage of plastic debris into the surrounding environment.

The average person in a low- or lower-middle-income country generates more than 50 times the plastic pollution of someone in a high-income country. That’s despite the fact that they generate four times less plastic waste overall.

Again, this is because many of these countries have much less developed collection and waste management infrastructure.

Around 0.5% of plastic waste ends up in the ocean

The world produces around 350 million tonnes of plastic waste each year.1

Estimates vary, but recent high-quality studies suggest that between 1 and 2 million tonnes of plastic enter the oceans annually.2

That means about 0.5% of plastic waste ends up in the ocean.

The chart shows that around one-quarter of plastic waste is mismanaged, meaning it is not recycled, incinerated, or stored in sealed landfills. This makes it vulnerable to polluting the environment.

Some of this is released into the environment, and a fraction of it reaches the ocean. This is shown as the last bar on the chart.

The probability that mismanaged plastic waste enters the ocean varies a lot across the world, depending on factors such as the location and length of river systems, proximity to coastlines, terrain, and precipitation patterns.

Note that the uncertainties around these estimates are large. Earlier estimates were as high as 8 million tonnes. However, other more recent studies have also found estimates in the range of around 1 million tonnes of plastic each year.3

Most ocean plastics come from low- to middle-income countries

Where do these ocean plastics come from?

As we saw earlier, mismanaged plastic waste — or rather, plastic pollution — tends to be much higher in low- to middle-income countries. This is because these countries tend to have poorer waste management infrastructure.

Mismanaged waste is at a much higher risk of polluting the environment and leaking into rivers and the ocean. The amount of mismanaged waste generated, combined with geographical factors such as proximity to shorelines, rivers, topography, and rainfall patterns, determines how much plastic flows into the ocean.

As shown in this map, most plastic flowing into the ocean today comes from middle-income countries, particularly across Asia.4

Research & Writing

October 05, 2023

How much plastic waste ends up in the ocean?

Around 0.5% of plastic waste ends up in the ocean. Most of it stays close to the shoreline.

May 01, 2021

Where does the plastic in our oceans come from?

Which countries and rivers emit the most plastic to the ocean? What does this mean for solutions to tackle plastic pollution?

October 11, 2022

Ocean plastics: How much do rich countries contribute by shipping their waste overseas?

Many countries ship plastic waste overseas. How much of the world’s waste is traded, and how big is its role in the pollution of our oceans?

October 05, 2023

Most plastic in the Great Pacific Garbage Patch comes from the fishing industry

More than three-quarters of floating plastic debris comes from fishing activities.

October 05, 2023

How much of global greenhouse gas emissions come from plastics?

Plastic production and disposal emits around 3% of global emissions.

Explore the data

How much plastic waste is generated

One metric commonly cited in discussions of plastics is how much waste is generated in the first place.

While this does not necessarily translate into how much pollution is generated (as we described above, and will come on to next), it gives us some idea of how much plastic is used, and how much waste countries will need to deal with if they want to manage this well.

In this chart, you can explore data on plastic waste generation, both in total quantities produced by a country or income group and per capita. This data is for municipal plastic waste generated by households only. It does not include waste generated by industry or construction, or oceanic sources such as fishing gear.

From this data, we see:

- Most of the largest producers of plastic waste are, unsurprisingly, the world’s most populous countries: China and India top the list. The United States, Brazil, and Indonesia complete the top five because they all have reasonably large populations and have relatively high levels of plastic use per person.

- When adjusted for population, countries across Europe, North America, and Oceania generate much more plastic waste per person than other regions.

- This is reflected in the breakdowns by income group: people in high-income countries generate more than four times as much plastic waste as those in low-income one, and twice as much as those in upper-middle income countries.

How plastic waste is managed

Whether plastic waste becomes a pollutant depends on how waste is managed.

This data explores rates of plastic pollution. Here, this is defined as plastic that is openly burned (generating toxic air pollution) or lost to the environment as solid debris.

In the chart, you can explore several indicators that compare rates across countries; show the breakdowns between open burning and debris pollution; and understand where this pollution is coming from (for example, is it because waste isn’t being collected by local services, or is it being poorly managed once it gets to a waste handling facility).

From this data, we see that:

- Countries across Asia, Sub-Saharan Africa, and South America tend to produce much more plastic pollution per person than those in Europe and North America. This is almost the opposite of the map of plastic waste generation.

- This is reflected in data for income groups: low-income countries produce almost 100 times more plastic pollution per person than high-income countries.

- This is true for both the open burning of plastic and debris that’s leaked into the environment.

- In the poorest countries, particularly across Sub-Saharan Africa and parts of Southeast Asia, a lot of pollution comes from waste that isn’t collected by any formal service.

- For others, particularly middle-income countries, most of this pollution is generated at the disposal stage: countries choose to manage their waste through open-burning, and open landfills where debris can escape.

- In high-income countries with effective waste management systems, most pollution comes from littering. However, these rates are not higher than they are in other parts of the world.

Plastic emitted into the ocean

Ocean plastics — particularly large floating masses of plastics — are often what come to mind when people think about plastic pollution. If we want to stop ocean pollution, we need to understand where it’s coming from.

This chart shows estimates of the amount of plastic pollution emitted to the ocean via rivers in each country.

This is partly determined by how much mismanaged plastic waste is generated. But it also depends on factors such as geography, topography, rainfall patterns, and river networks. Plastic pollution in a landlocked country is less likely to make it to the ocean than in one on a coastline with lots of large river outlets. In this map, you can see the probability that mismanaged waste leaks into the ocean in each country.

From this data, we see that:

- The five largest sources of ocean plastics are the Philippines, India, Malaysia, China, and Indonesia. These are all countries with large populations, significant quantities of mismanaged waste, and geographical attributes that mean plastics can easily reach coastlines via rivers.

- Combined, these five countries contribute around 70% of the world’s ocean plastics from rivers.

- When we look at ocean plastic emissions per person, we see a stark contrast across regions. Europe and North America tend to have small emissions, whereas countries across Asia, Africa, and South America have much higher rates. This is largely down to the effectiveness of waste management systems.

- On a per capita basis, the Philippines is still the largest emitter, but the other leaders are mostly small island states or countries close to the coastline.

The trade of plastic waste between countries

It might seem odd that countries would agree to import plastic waste from other countries, but many do so for the cheap materials or to feed specific manufacturing processes.

There is an environmental risk, though: countries do not only contribute to plastic pollution through their mismanaged domestic waste. If they export plastic waste to countries with poorer waste management, then they could also be indirectly contributing to the problem.

How significant is the trade of plastic waste?

This data shows the trade between countries, both in terms of imports, exports, and net exports (the balance of the two). What you might notice is that countries can be both importers and exporters; this is because they may import a specific type of plastic while selling other types to others.

From this data, we see that:

- Globally, around 3.2 million tonnes of plastic waste were traded between countries in 2024. For context, the world generated around 350 million tonnes of plastic waste, which means that just under 1% of plastic waste was traded.

- Around 90% of this waste was exported from high-income countries. However, high-income countries were also the largest importers of plastic waste, which suggests they are trading a lot of these plastics between each other, rather than sending them to low-income countries.

- Global trade in plastics has fallen sharply from its peak in 2016, largely because of China’s 2018 ban on imports.

- The largest net exporters of plastic waste per person are all countries in Europe, with the exception of Japan and New Zealand.

Featured Data on Plastic Pollution

Data Insights on Plastic Pollution

Endnotes

This includes municipal plastic waste from households, plus waste from industry and construction. Further down on this page, you will find data on municipal plastic waste only, which amounts to around 250 million tonnes.

This data comes from the OECD’s Global Plastic Outlook.

OECD (2022), Global Plastics Outlook: Economic Drivers, Environmental Impacts and Policy Options, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/de747aef-en.

Meijer, L. J., Van Emmerik, T., Van Der Ent, R., Schmidt, C., & Lebreton, L. (2021). More than 1000 rivers account for 80% of global riverine plastic emissions into the ocean. Science Advances, 7(18), eaaz5803.

Meijer, L. J., Van Emmerik, T., Van Der Ent, R., Schmidt, C., & Lebreton, L. (2021). More than 1000 rivers account for 80% of global riverine plastic emissions into the ocean. Science Advances, 7(18), eaaz5803.

But this was not always the case: richer countries have been polluting the oceans for longer. If we look at accumulated stocks of plastics in the ocean, higher-income countries across Europe and North America play a larger role than they do today.

Cite this work

Our articles and data visualizations rely on work from many different people and organizations. When citing this topic page, please also cite the underlying data sources. This topic page can be cited as:

Hannah Ritchie, Veronika Samborska, and Max Roser (2023) - “Plastic Pollution” Published online at OurWorldinData.org. Retrieved from: 'https://ourworldindata.org/plastic-pollution' [Online Resource]BibTeX citation

@article{owid-plastic-pollution,

author = {Hannah Ritchie and Veronika Samborska and Max Roser},

title = {Plastic Pollution},

journal = {Our World in Data},

year = {2023},

note = {https://ourworldindata.org/plastic-pollution}

}Reuse this work freely

All visualizations, data, and code produced by Our World in Data are completely open access under the Creative Commons BY license. You have the permission to use, distribute, and reproduce these in any medium, provided the source and authors are credited.

The data produced by third parties and made available by Our World in Data is subject to the license terms from the original third-party authors. We will always indicate the original source of the data in our documentation, so you should always check the license of any such third-party data before use and redistribution.

All of our charts can be embedded in any site.