The end of tuberculosis that wasn’t

In the 1980s, many thought tuberculosis was on the path to elimination. In reality, more were dying from the disease than ever.

In the late 1980s, many thought the fight against tuberculosis (TB) had been won. A disease that had plagued humans for at least 9000 years was on the path to being eliminated.1 The world knew what caused it, how to screen for it, and finally had effective antibiotics to treat it.

By the mid-20th century, tuberculosis in the United States and Europe had already declined thanks to improved nutrition and living conditions. Once treatments arrived in the 1950s, deaths tumbled: by the late 1980s, they had fallen by over 90% in the United States.2 The United States was so confident that tuberculosis would gradually disappear that the US Congress stopped direct government funding for TB programs in 1972.

You have to know the history of tuberculosis to fully appreciate what a victory that would be. The disease, which spreads from person to person via water droplets, was once one of the biggest killers in many parts of the world. Without treatment, getting it was practically a death sentence.3 It was responsible for as much as one-quarter of deaths in the United States and Europe during parts of the 19th and early 20th centuries. Go back to 1750s London, and 1% of the population were dying from tuberculosis every year.

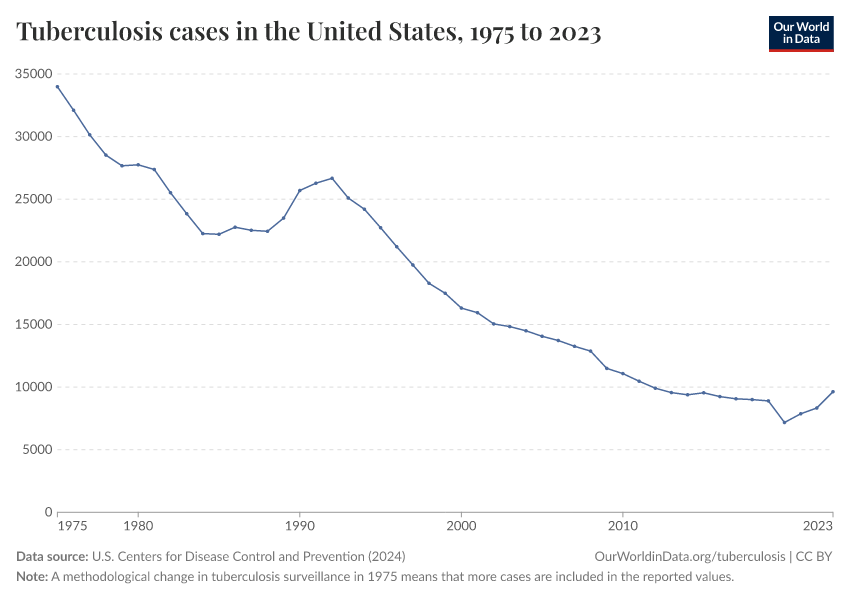

Fast-forward to the 1980s, and just when TB seemed to be on its way out in the United States, there was a bump in the number of cases and the number of deaths. You can see this rise in the second half of the 1980s in the chart below.

As a story in the Los Angeles Times put it:

“We really thought (tuberculosis) was going the way of polio. Up until 1988, the TB rate was going down every year. And then all of a sudden, the rate started increasing and everyone was caught off guard.”

The New York Times ran the following headline in 1985.

In this article, we cover the reality of tuberculosis in the 1980s and 1990s at two different levels. First, we explain why there was a temporary reversal in the United States. Second, we zoom out to understand the world’s re-evaluation of the scale of the TB problem at a global level.

Tuberculosis made a temporary comeback in the United States and other countries

Three factors raised concerns about the resurgence of tuberculosis in the United States and rich countries in Europe.

The emergence of the HIV/AIDS epidemic

The first was the HIV/AIDS epidemic, which began in the 1980s and continued to grow throughout the 1990s. In the chart below, you can see the steep rise in the number of Americans dying from HIV/AIDS over these decades.

What did this have to do with tuberculosis? Well, scientists and health experts started to see that rates of TB cases and deaths were higher in those with HIV than in the general population. This is because those with HIV have a weakened immune system, which means tuberculosis bacteria can thrive, and turn an “inactive” latent tuberculosis infection into an “active” one.4 After malnutrition, having HIV is the leading risk factor for developing tuberculosis. This introduced a new driver of infection that Americans had not faced in the 1950s, 60s, or 70s when deaths were falling steeply.

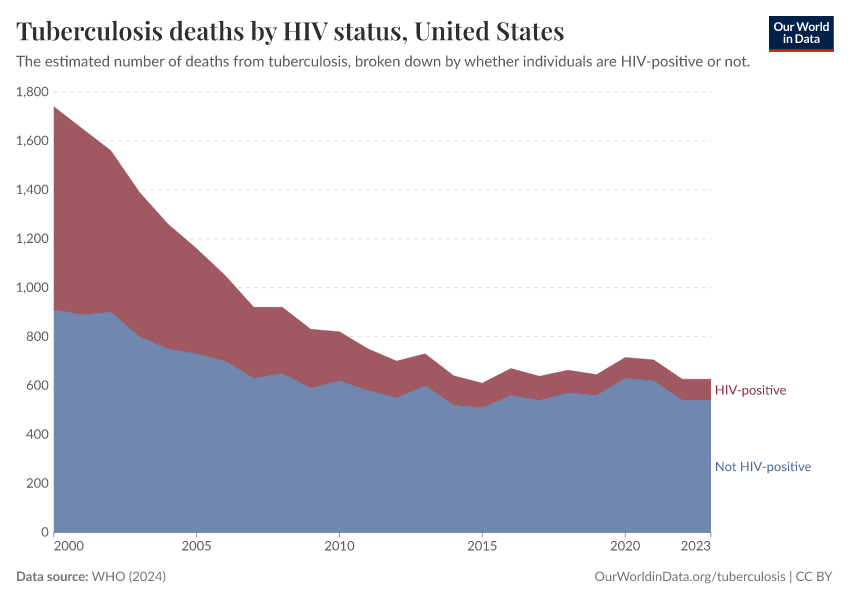

Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, the share of Americans with tuberculosis who also had HIV rose steeply. HIV-positive patients weren’t just more likely to develop active tuberculosis — they were far more likely to die from it. In 1993, among TB patients with known HIV status in the US, nearly half were HIV-positive, but they accounted for 82% of TB deaths.

As late as the year 2000, almost as many Americans dying from tuberculosis had HIV as didn’t. You can see this in the chart below. That fact is staggering, given that just 0.5% of Americans had HIV at the time. In other words, 0.5% of the population accounted for half of tuberculosis deaths, with the other half coming from the remaining 99.5%.

But as you can also see in the chart, even more aggressive controls on TB and HIV meant that this share has fallen a lot over the last decades.

The rise of drug-resistant tuberculosis

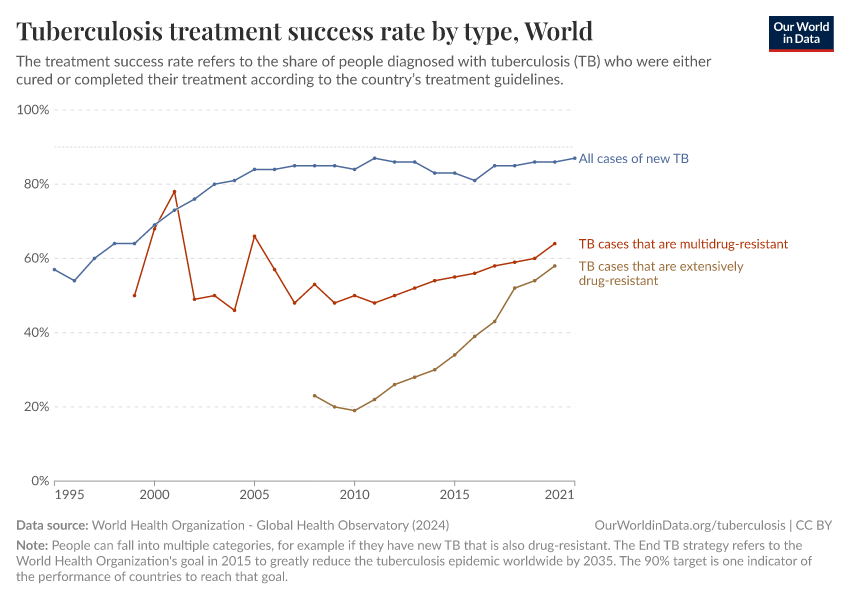

The second factor causing alarm was the rise of drug-resistant tuberculosis. In the 1950s, scientists had discovered a combination of antibiotics that were extremely effective in treating patients with TB. However, over time, it became clear that some individuals were not responding as positively to treatment. This was because of the development of tuberculosis infections that were drug-resistant.5 These cases are much more expensive to treat and have a much lower success rate. This is still the case today, as you can see in the chart below, and the odds of a successful treatment were likely even lower in the 1990s.

Higher rates of TB in foreign-born populations

The third, which will lead us on to the global part of the narrative change, was the higher rates of TB in the foreign-born population.

In the US, TB rates among immigrants were almost four times higher than among native-born residents in the 1980s.6 Most of these cases were diagnosed within five years of arriving in the US, which suggests that many had moved with an existing infection.7 Of course, people were migrating to the US before the 1980s, while TB rates were still falling. However, a few things changed before and during that period and could have had an impact. First is the 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act, which opened immigration opportunities to migrants from other parts of the world. Before 1965, most immigrants to the US came from Europe, where TB rates had already dropped dramatically. Second, rates of immigration increased substantially from the 1970s to the 1990s. Not only were more people moving to the US, but they were often moving from countries where tuberculosis rates were high.

This was also true in many European countries. Half of TB cases in the Netherlands and Scandinavia were among foreign-born residents (despite immigrants making up a much smaller share of the population).8

This shouldn’t have been that surprising. Richer countries had invested significant amounts into screening and treating the disease, which many other countries didn’t have the resources for, or detailed data to understand the scale of the problem. Having people move from high-burden TB countries to lower-burden ones would naturally introduce new cases into the population.9

Infectious diseases like tuberculosis do not respect borders. As long as a disease is common amongst the global population, individual countries will always be at risk of a resurgence. If countries were to eliminate tuberculosis once and for all, it had to be a global effort, not just a national one.

A key issue is that in the 1980s, there was a severe lack of data about the TB burden in low- and many middle-income countries. But, of course, not having data measuring a problem does not mean it doesn’t exist. Still, inadequate measurement meant that tuberculosis was underestimated and neglected. Only when better estimates became available did people wake up to the true scale and focus more on doing something about it.

From a shrinking problem to a global health emergency

Despite having easy ways to screen for TB and highly effective treatments, the world was losing its battle against tuberculosis in the 1990s. The WHO pronounced that more people died from TB in 1995 than in any year in history.10 While the US and some countries in Europe had decades of detailed records of cases, deaths, and risk factors, much of the rest of the world was blind to the scale of the problem. It wasn’t until the early 1990s that the World Health Organization (WHO) carried out the first comprehensive estimate of the global burden of TB. Of course, this involved much more than simply counting up known cases of TB; it also required modelling and expert judgement on the true spread and mortality of the disease.

In 1990, there were an estimated 8 million new cases of active TB, and nearly 3 million deaths. That was more than double the number of cases that had been recorded and reported to the WHO. Tuberculosis was not a problem on the way out; it often went unseen, leading to a huge underestimation of its true size. One of history’s biggest killers was killing more people than ever.

As Dr. Hiroshi Nakajima, the WHO Director-General then, put it: "Not only has TB returned, it has upstaged its own horrible legacy".

In 1993, the WHO declared tuberculosis a “global health emergency”.

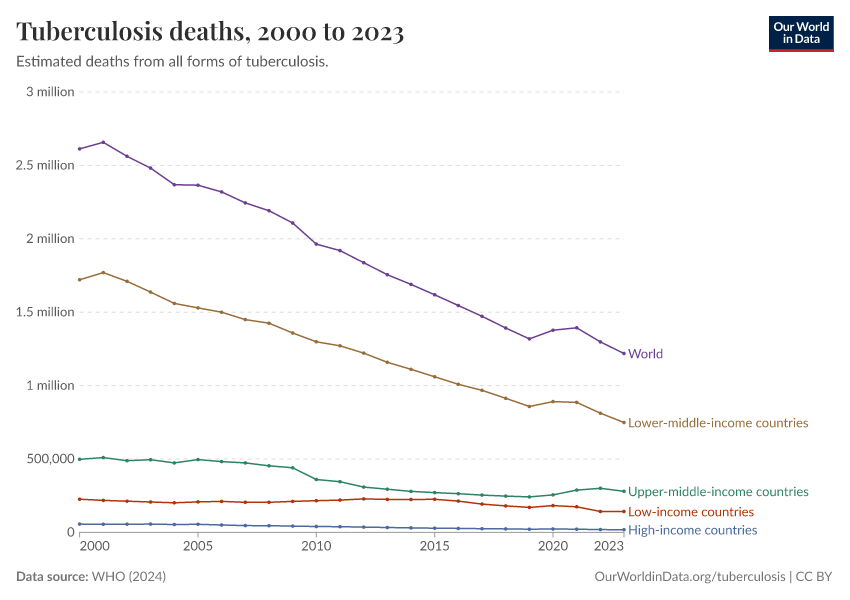

The world has made progress in reducing the burden of TB since then. In 2000, around 2.6 million people were still dying from tuberculosis each year. That has more than halved to 1.3 million. You can see this in the chart below.

But with over a million deaths each year, tuberculosis is still a huge killer. The fact that so many still die from this preventable disease, particularly in lower-income countries, is still a gross failure to me.

Robert Koch, who discovered the tubercle bacillus, would be disappointed by our inability to finally overcome this disease. As early as 1905, he was confident that the war against it would be won:11

“The struggle [against tuberculosis] has caught hold along the whole line and enthusiasm for the lofty aim runs so high that a slackening is no longer to be feared. If the work goes on in this powerful way, then the victory must be won.”

120 years on, and we’re still not close, despite having the tools we need to do so.

In the final article in this three-part series, we will examine today’s burden of TB in more detail and what is needed to achieve what the US and Europe have done everywhere.

We need good data to understand the scale of global problems and how we tackle them effectively

This wake-up to the tuberculosis crisis was a perfect example of two points that are core to our work at Our World in Data.

The first is about how crucial good data is for understanding the scale, distribution, and directional change of the big problems the world faces. You cannot understand the situation of tuberculosis from personal situations or anecdotes. You also can’t understand the global problem by extrapolating progress in the United States and Europe to the rest of the world.

Indeed, a lot of progress had been made in high-income countries, but tuberculosis was still a devastating problem elsewhere. It still is.

It wasn’t until health experts provided new and better estimates of the global burden of tuberculosis that it was put back on the agenda. Without this data, it might not be. Tuberculosis would still be spreading rapidly, and killing many millions every year; the world would just be blind to the real cause.

This renewed understanding of the scale of the problem had obvious knock-on impacts for policymaking and priority-setting. It can be partly attributed to the decline in deaths we’ve seen since then. If you know where tuberculosis is spreading and its risk factors, you can invest money in the right places, ensuring that communities have the testing technologies and treatments they need.

The second point is complacency. At Our World in Data, we often use historical data to show that progress on many problems is possible. But we also try to make clear that progress is in no way inevitable. Even on a good path, there is always the risk of backsliding. This was the case with tuberculosis in the late 1980s: many expected cases and deaths to keep falling, but they didn’t. Progress stalled, then temporarily reversed.

What’s crucial, though — and this links back to my first point — is that close monitoring and transparent data can often alert people to these reversals early. High-quality monitoring of TB cases and deaths in the US meant that the rise was quickly detected, action could be taken, and the backslide was only temporary. What’s more: good data on who was dying from tuberculosis helped to identify the reasons why trends had turned: it was clear that there was a link to HIV, and that treatments were not working for some people, those who had a drug-resistant infection. Without this detailed data, it would have taken the US far longer to notice a reversal in the trend and identify why this was happening.

These lessons apply to so many issues, not just tuberculosis. Without good data, we are often blind to the scale of the world’s problems. But when we fail to act on that data, we effectively close our eyes and turn the other way.

Acknowledgments

We thank Saloni Dattani, Edouard Mathieu, and Simon van Teutem for valuable comments and feedback on this article.

Once a leading killer, tuberculosis is now rare in rich countries — here’s how it happened

As much as one quarter of deaths in Europe and the United States were once from tuberculosis.

The end of tuberculosis that wasn’t

In the 1980s, many thought tuberculosis was on the path to elimination. In reality, more were dying from the disease than ever.

The world left its fight against tuberculosis unfinished — how can we complete the job?

If we get it right, the world could save more than 1.2 million lives every year.

Endnotes

We know our relationship with tuberculosis goes back at least 9000 years because there is archaeological evidence of tuberculosis lesions in bone samples from the Middle East. Hershkovitz, I., Donoghue, H. D., Minnikin, D. E., Besra, G. S., Lee, O. Y., Gernaey, A. M., ... & Spigelman, M. (2008). Detection and molecular characterization of 9000-year-old Mycobacterium tuberculosis from a Neolithic settlement in the Eastern Mediterranean. PloS one, 3(10), e3426. Gibbons (2021). How tuberculosis reshaped our immune systems. Science.

In 1953, 19,707 people in the US died from tuberculosis. By 1987, this had fallen to 1755. That’s a reduction of around 91% [(19,707 - 1755) / 19,707 * 100 = 91%].

This data comes from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Here I’m talking about active cases of tuberculosis. Many more people have latent (or “inactive”) TB and will never suffer any symptoms.

Bell, L. C. K., & Noursadeghi, M. (2018). Pathogenesis of HIV-1 and Mycobacterium tuberculosis co-infection. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 16(2), 80–90. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro.2017.128

Bruchfeld, J., Correia-Neves, M., & Källenius, G. (2015). Tuberculosis and HIV Coinfection. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Medicine, 5(7), a017871. https://doi.org/10.1101/cshperspect.a017871 Many people in the world have been infected with latent or inactive tuberculosis. This will usually never develop into an active infection that causes severe symptoms.

Farhat, M., Cox, H., Ghanem, M., Denkinger, C. M., Rodrigues, C., Abd El Aziz, M. S., ... & Pai, M. (2024). Drug-resistant tuberculosis: a persistent global health concern. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 22(10), 617-635.

McKenna, M. T., McCray, E., & Onorato, I. (1995). The epidemiology of tuberculosis among foreign-born persons in the United States, 1986 to 1993. New England Journal of Medicine, 332(16), 1071-1076. It’s still the case today that TB rates are higher in those born outside of the US: Menzies, N. A., Hill, A. N., Cohen, T., & Salomon, J. A. (2018). The impact of migration on tuberculosis in the United States. The International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease, 22(12), 1392-1403.

This was exacerbated by the fact that poverty is a key risk factor for TB and many immigrants had lower incomes and lived in communities with higher levels of poverty.

Raviglione, M. C. (2003). The TB epidemic from 1992 to 2002. Tuberculosis, 83(1-3), 4-14.

This is potentially less of a risk today. Some high-income countries provide TB screening to immigrants from high-burden TB countries who are entering the country. If diagnosed with TB, they are then put on treatment. This reduces the risk of introducing untreated active cases into the general population.

The WHO estimated that in the year 1900, two to three million people were dying from tuberculosis globally.

This quote was part of Robert Koch’s Nobel Lecture in 1905.

Cite this work

Our articles and data visualizations rely on work from many different people and organizations. When citing this article, please also cite the underlying data sources. This article can be cited as:

Hannah Ritchie and Fiona Spooner (2025) - “The end of tuberculosis that wasn’t” Published online at OurWorldinData.org. Retrieved from: 'https://archive.ourworldindata.org/20251217-162706/the-end-of-tuberculosis-that-wasnt.html' [Online Resource] (archived on December 17, 2025).BibTeX citation

@article{owid-the-end-of-tuberculosis-that-wasnt,

author = {Hannah Ritchie and Fiona Spooner},

title = {The end of tuberculosis that wasn’t},

journal = {Our World in Data},

year = {2025},

note = {https://archive.ourworldindata.org/20251217-162706/the-end-of-tuberculosis-that-wasnt.html}

}Reuse this work freely

All visualizations, data, and code produced by Our World in Data are completely open access under the Creative Commons BY license. You have the permission to use, distribute, and reproduce these in any medium, provided the source and authors are credited.

The data produced by third parties and made available by Our World in Data is subject to the license terms from the original third-party authors. We will always indicate the original source of the data in our documentation, so you should always check the license of any such third-party data before use and redistribution.

All of our charts can be embedded in any site.